Looking at Michael Tomasello’s Book (2008) “Origins of Human Communication” (Part 1 of 12)

0083 In 2008 AD, Michael Tomasello, then co-director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, publishes the work before me (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts).

This book is the second marker in Tomasello’s intellectual journey. I start following his journey with Looking at Michael Tomasello’s Book (1999) “The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition” (appearing in Razie Mah’s January 2024 blog). That is the first marker.

0084 The second marker starts as an academic presentation in 2006. His Jean Nicod Lectures, in Paris, concerns his work on great ape gestural communication, human infant gestural communication and human children’s language development. These lectures attempt to construct one coherent account of the evolution of hominin communication.

Oh, that terminology. Where Tomasello inscribes, “human”, I say, “hominin”.

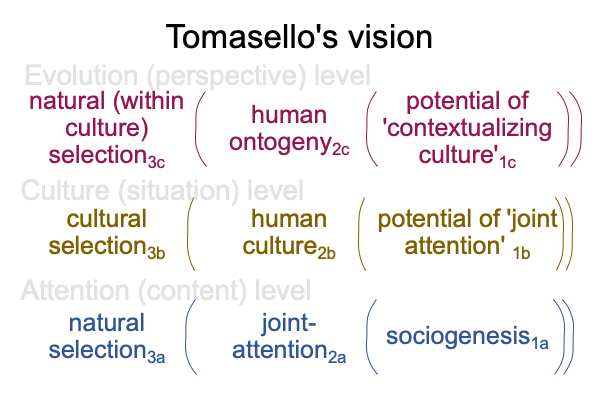

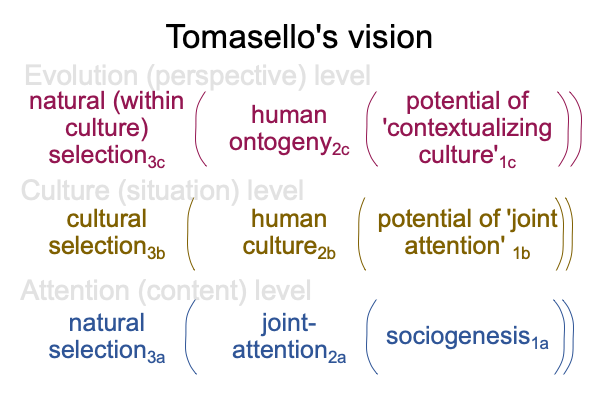

0085 From my examination at the first marker, I already have a guess about Tomasello’s vision.

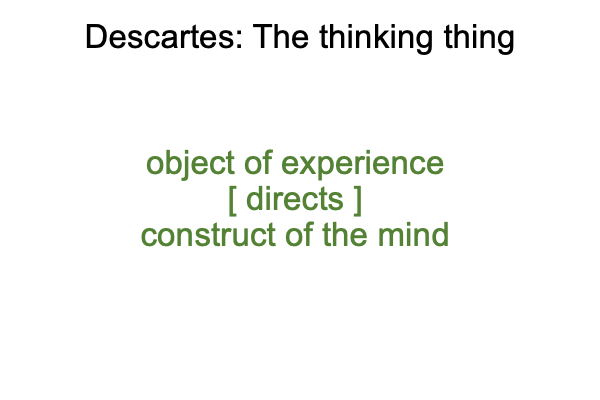

Here is a picture.

0086 Note that the titles of the levels have changed.

Also note that human ontogeny2c or models of child development currently built by psychologists2c, associates to phenotypes and genetics. Joint attention2a or models in evolutionary psychology concerning hominin cognition2a,associates to adaptations and natural history.

0087 Tomasello uses the word, “origins”, in his title. Does this suppose that human communication may be regarded as a phenotypic trait or as an adaptation? Or maybe, the conjunction is “and”.

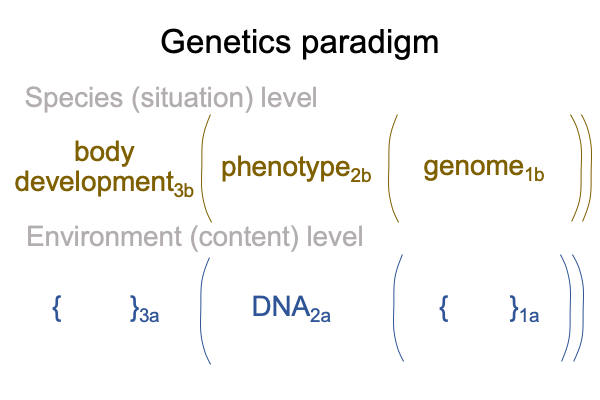

In the above figure, I get the idea that the phenotype virtually contextualizes the adaptation. But, that is not really the case. The phenotype2b virtually situates a species’ or individual’s DNA2a.

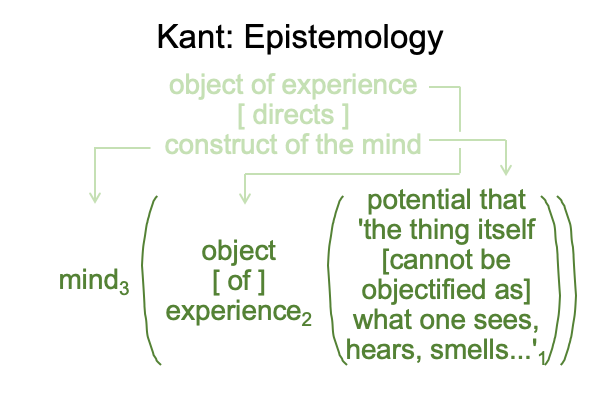

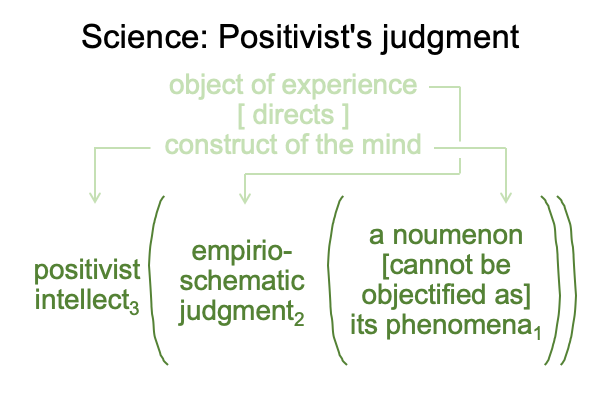

Here is a diagram.

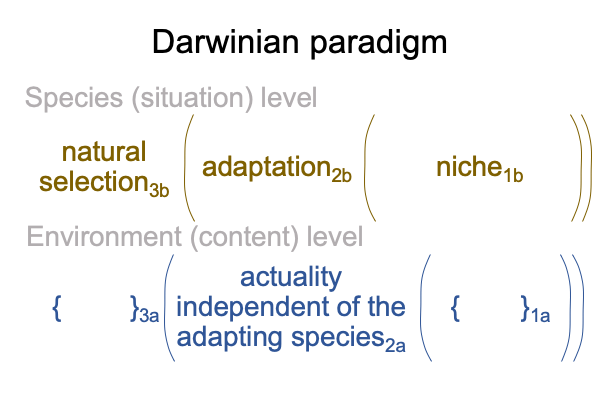

0088 Not surprisingly, this diagram in genetics has the same two-level relational structure as Darwin’s paradigm for natural history.

0089 What does this imply?

A mystery stands at the heart of evolutionary biology.

The adaptation is not the same as the phenotype.

Yet, together, they constitute a single actuality, which may be labeled a genus, a species or an individual.

Two category-based nested forms intersect in the realm of actuality. It is like two streets that meet. The intersection is constituted by both streets. As far as traffic goes, intersections are sites of dangerous contradictions. Traffic from one street should not collide with traffic from the other street. I suppose that the intersection of adaptation and phenotypecarries irreconcilable contradictions as well.

0090 Perhaps, Tomasello’s vision may be resolved by considering both joint attention2a and human ontogeny2c as adaptations, even though the latter is technically, phenotypic.

I suggest this because selection is the normal context for all three levels in Tomasello’s vision. Since natural selection goes with adaptation, the vision is one of natural history.

0091 That implies that the potentials for all three levels are like niches.

Human ontogeny2c is an adaptation that emerges from and situates the potential of human culture2b, where human culture2b is like an actuality independent of the adapting species of individuals undergoing development3c.

Human culture2b is like an adaptation that emerges from and situates the potential of joint attention2a, where joint attention2a is like an actuality independent of the adapting ways of doing things3b.

Joint attention2a is like an adaptation that emerges from and situates sociogenesis1a, where sociogenesis1a is the potential of… what?… I have run out of actualities independent of the adapting species.

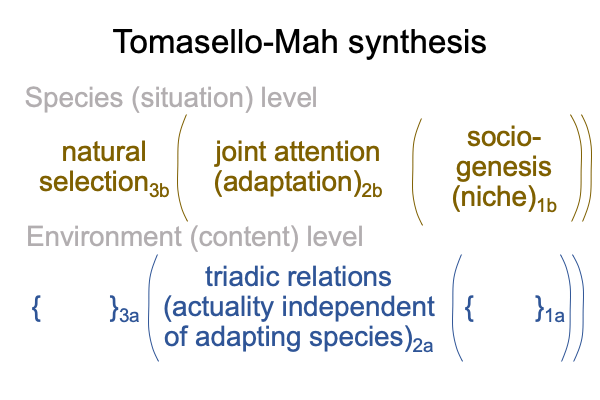

0092 Here is where the foundational Tomasello-Mah synthesis enters the picture.

Ah, so here is a problem.

Tomasello’s vision of the origins of human communication conceals the actuality underlying sociogenesis1a, the potential1a giving rise to joint attention2a. The human niche is the potential of triadic relations.

0093 What about the subscripts in the preceding paragraph?

They belong to Tomasello’s vision.

0094 This subscript business can be confusing.

To me, the concealment in Tomasello’s vision is not necessarily a drawback. Rather, it presents an opportunity to re-articulate Tomasello’s arc of inquiry using the category-based nested form and other triadic relations.

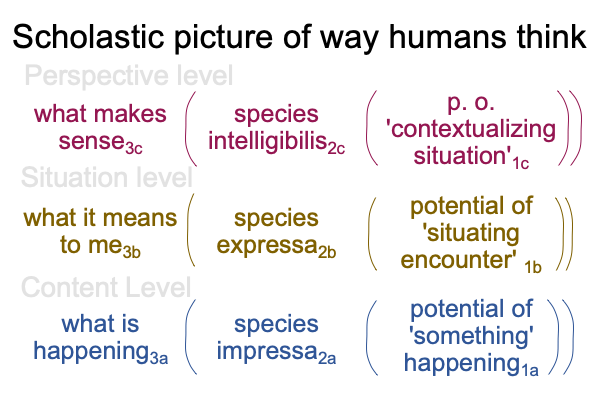

0095 In the prior series of blogs, examining a book published in 1999, I introduced an interscope for the way humans think that derives from work by medieval schoolmen, the so-called “scholastics” of the Latin Age.

Here is a picture of the scholastic version of how humans think, packaged as a three level interscope.