Looking at Peeter Torop’s Article (2017) “Semiotics of Cultural History” (Part 5 of 11)

1013 Well, that is close enough to science that a scholar schooled in Slavic languages and literature gets.

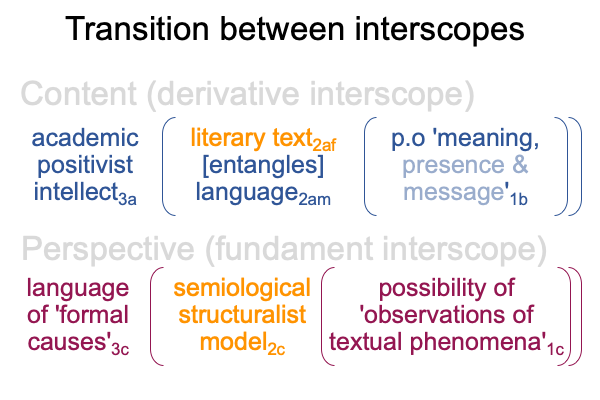

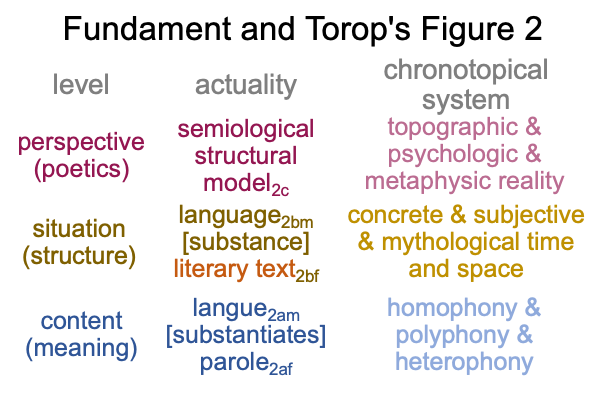

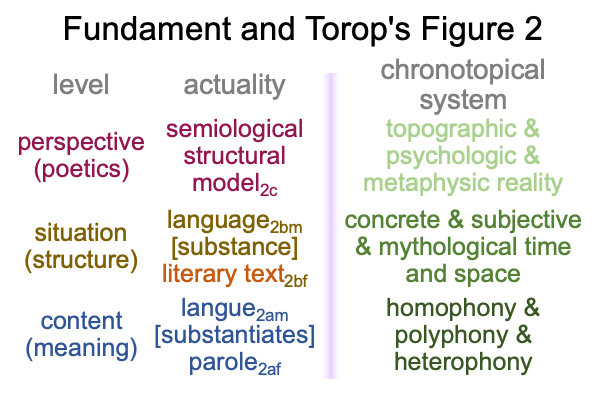

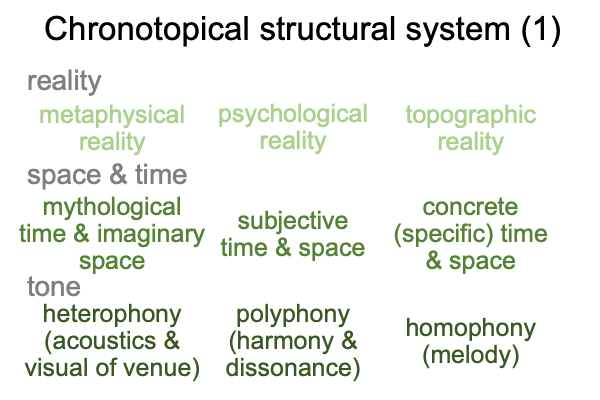

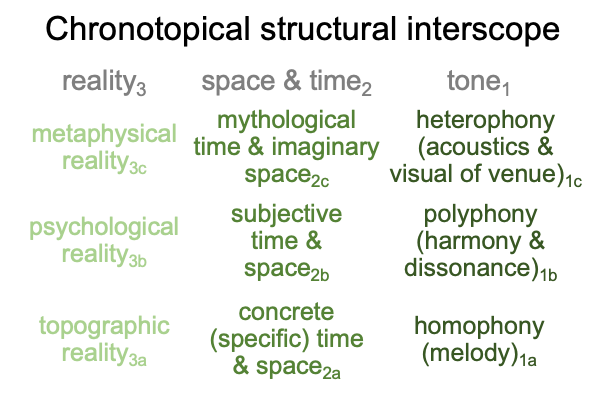

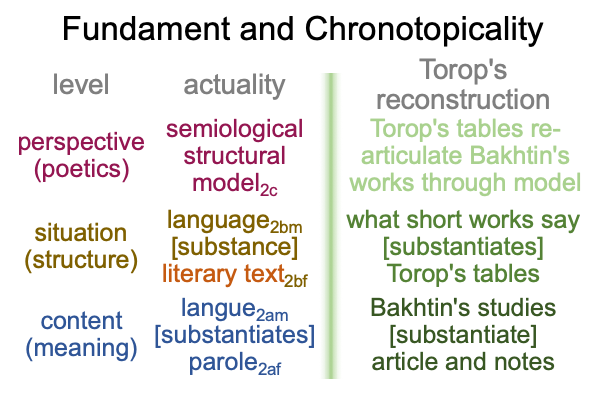

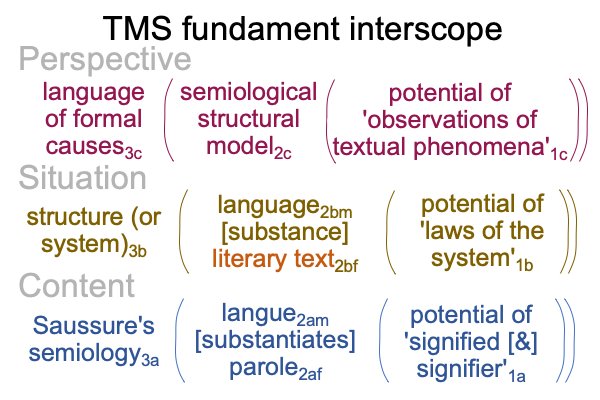

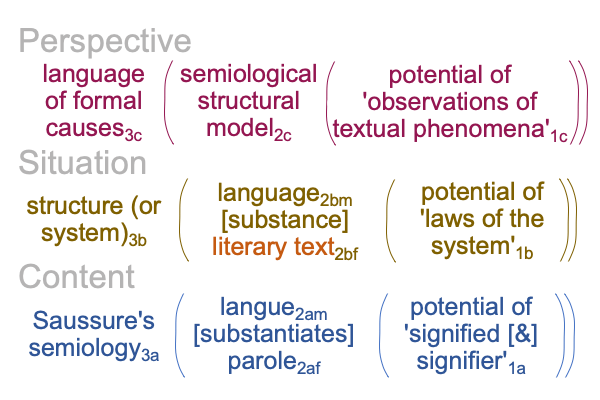

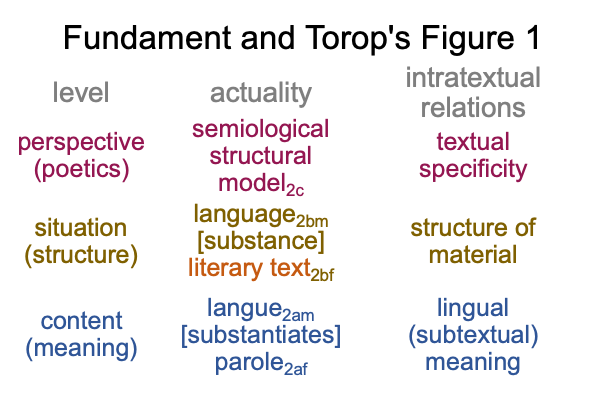

I call the resulting interscope, “fundament”, because it takes the inquirer from the mother tongue2a through the composition of the text2b, to a model2c that is based on the nature of signs3a and on the way that any particular genre, style, fashion, and artistic expression constitutes a system3b bound by rules1b. The fundament applies to a wide range of “languages” in so far as a specific style of artistic expression displays distinct elements, or forms2b(2a), that correspond to mental thoughts2a and linguistic matter2b.

1014 Here is a picture of the fundament interscope.

1015 Perhaps, most striking is the Aristotelian character of the fundament. The content-level hylomorphe2a is universal. The situation-level hylomorphe2b should be intelligible. The perspective-level model2c is a relation that brings the intelligibility of the situation-level hylomorphe2b into relation with the universality of the content-level hylomorphe2a.

The fundament seems to be an exercise in aesthetics as much as modern science.

Juri Lotman labels it, “Russian theory”.

1016 Is it any coincidence that Russian Theory spontaneously constellates at the same time as Husserl’s and Heidegger’s phenomenology? Both strive to assess what the noumenon must be, given the phenomena of matter and form.

1017 Phenomenology re-articulates technical achievements (such as a particular style of architecture) as social things, arriving at noumena whose phenomena engage the social sciences.

See the e-book course, Phenomenology and the Positivist Intellect, by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues. Also see the three part e-work, Biosemiotics as Noumenon.

1018 Russian theory re-articulates literary achievements (as well, all the modern arts) in Slavic civilization as… um… semiological and structural judgments2c, lingering like Byzantine shadows of Aristotle in the Marxist-illuminated hallways of Moscow and Tartu Universities.

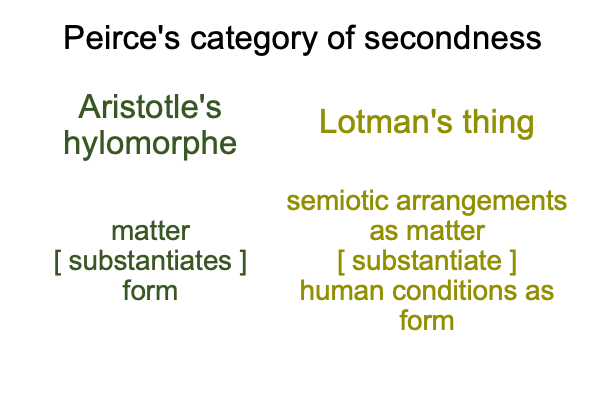

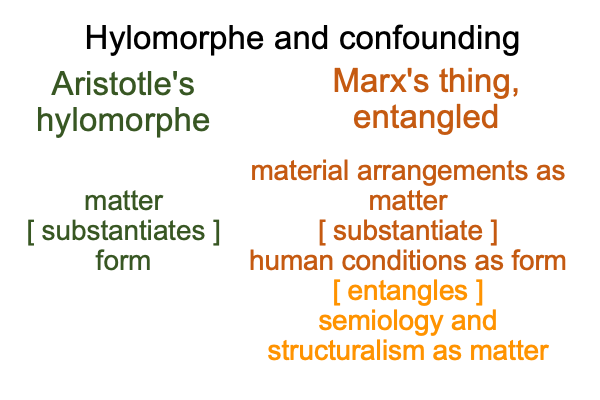

1019 Indeed, the fundament is so… um… profound that Marx’s thing gets entangled in semiotics as matter.

1020 How confounding.

The dangers of this confounding are palpable in the interview with Vyacheslav Ivanov, appearing in Kalevi Kull and Ekaterina Velmezova (eds.), Sphere of Understanding: Tartu Dialogues with Semioticians (2025, Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston, pages 47-68).

1021 One can only admire Lotman’s bravado when it comes to the bureaucratic morons, who are both culturally Slavs (having an intuitive Orthodox appreciation of entanglement) and indoctrinated not be be Slavs (by the Marxist insistence that Christian superstition is scientific nonsense) and are therefore already conflicted.

Sometimes, morons can advance science by simply not resolving their conflictions.

1022 But, that is another story.

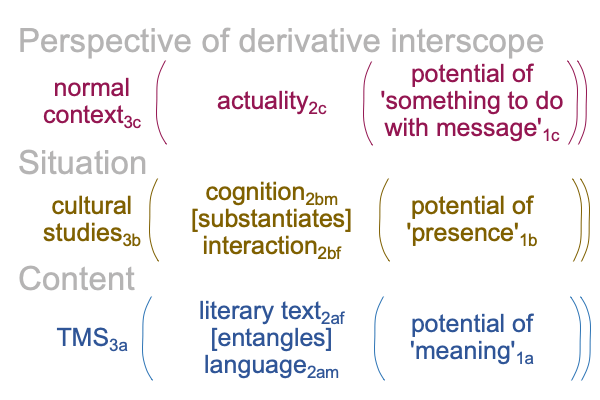

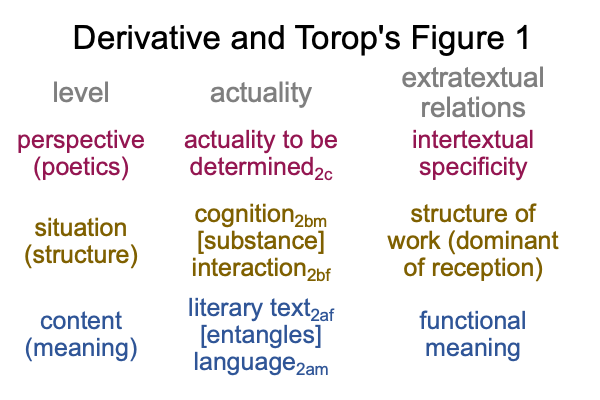

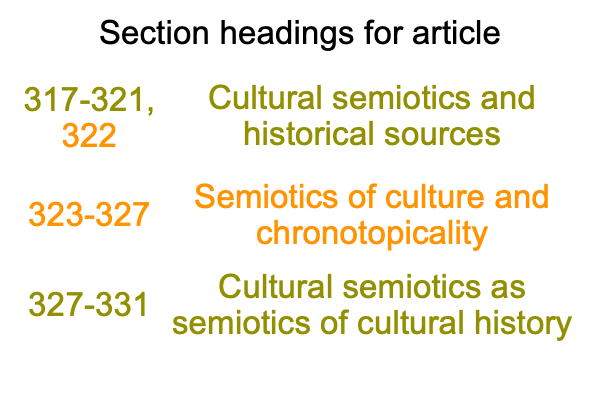

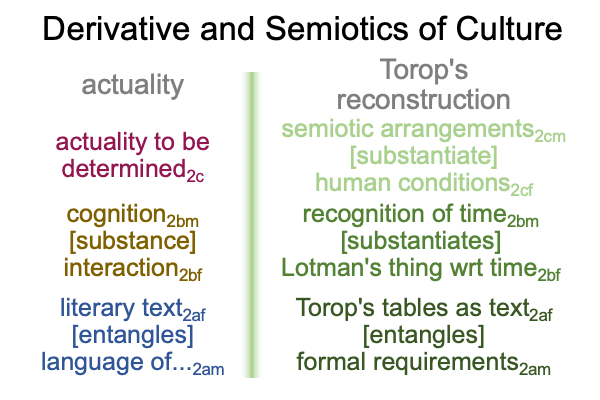

1023 Here, on page 321 of the text under examination, Torop shifts into the technical details of a literary order. He offers a table, listing levels for intratextual and extratextual relations. Intratextual relations concern the text itself. Extratextual relations concerns what type of text it is.

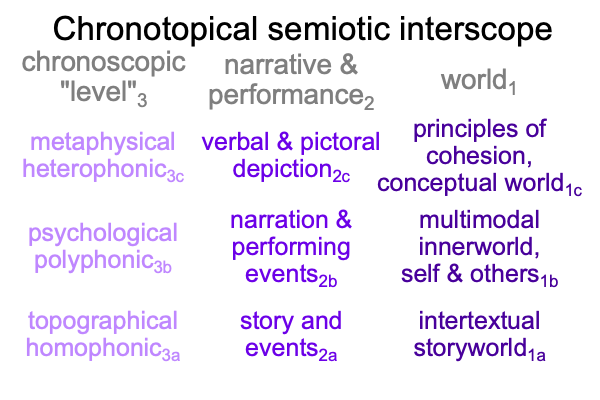

1024 The actualities of the fundament interscope compare well with Torop’s intratextual relations.

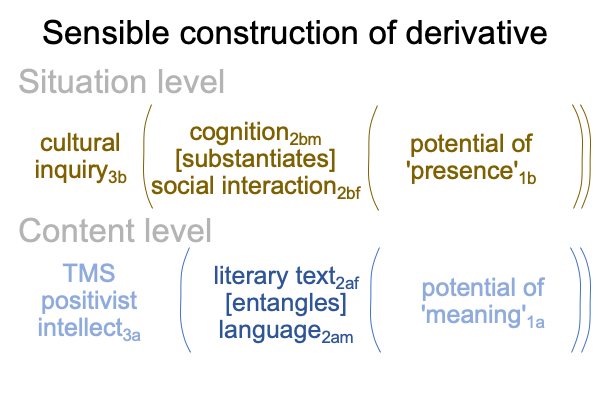

1025 On the content level of word and meaning, Saussure’s dyadic actuality compares to subtextual and lingual meanings. In short, an author must craft thoughts2am into words2af.

1026 On the situation level of the structure of the textual material, the dyad of {language as matter2bm [substantiates] the literary text as form2bf} compares to what Torop calls “the structure of material (dominant element or level)”.

1027 What does the term in parentheses imply?

Does “the dominant element or level” represent the normal context of structure (or sign-system)3b operating on the potential laws of the system1b?

For example, a text on history may be an epic tale, a historical analysis or a fairy tale. Each manifests a different structure3b and lawfulness1b.

1028 On the perspective level of poetics, a semiological structuralist model2c compares to textual specificity. To me, both actualities contain some sort of judgment.

For example, let me propose a thesis in the humanities that consists of concatenating plagiarized passages from various experts on a particular topic. When the submission is debated by the student’s faculty committee, they may consider the fact that the passages were chosen by the student may represent a unique intellectual advancement offered by the student. In comparison to the visual arts, the submitted text is a collage.

The problem is obvious. A submission on say, a Slavic work of literature, cannot be labeled a “thesis” when it is really the textual equivalent to a collage.

1029 So, Torop’s label of “poetics” for the perspective level conveys a certain irony.