Looking at Steven Mithen’s Book (2024) “The Language Puzzle” (Part 2 of 23)

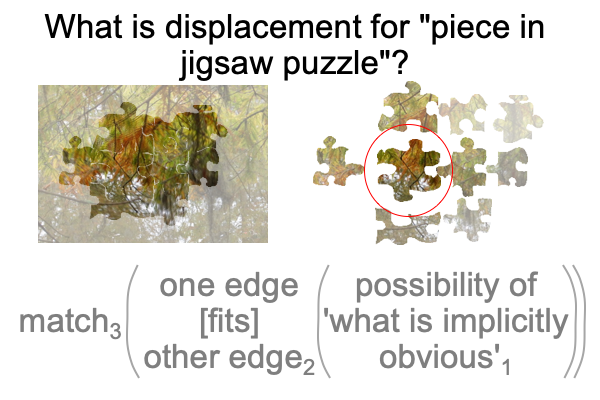

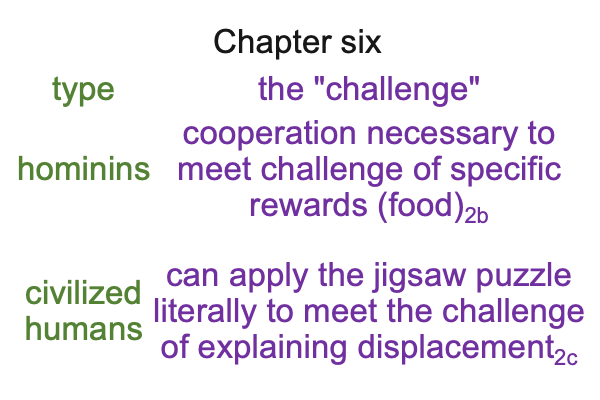

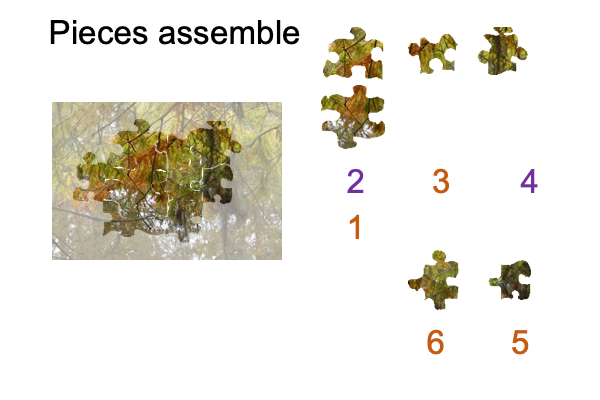

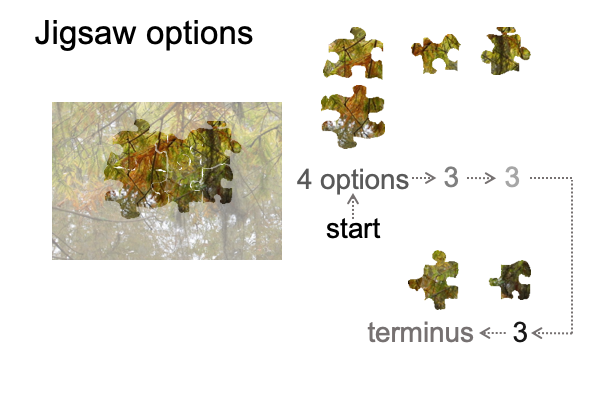

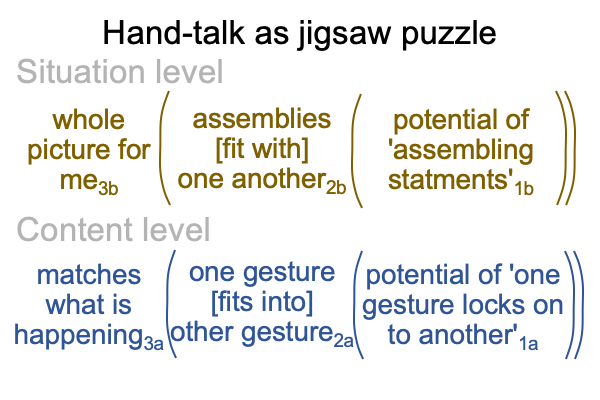

0007 Imagine a jigsaw puzzle.

In a way, a jigsaw puzzle is a purely relational structure.

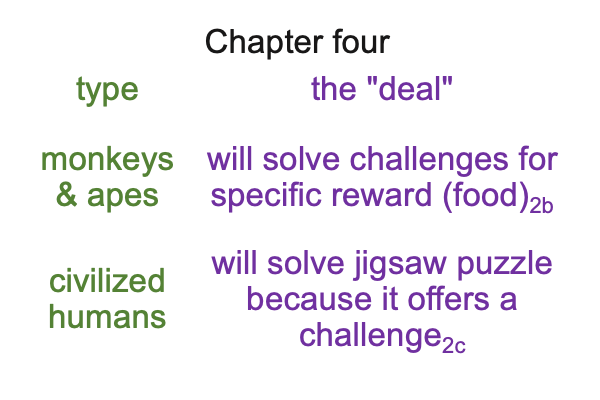

0008 In order to solve the puzzle, one must dyadically connect each puzzle piece to other pieces. Sometimes the image on a puzzle piece offers a clue. Other times, an unusual edge catches the eye. Either way, one edge of one puzzle piece will fit with one edge of another piece in a way that is intuitively obvious.

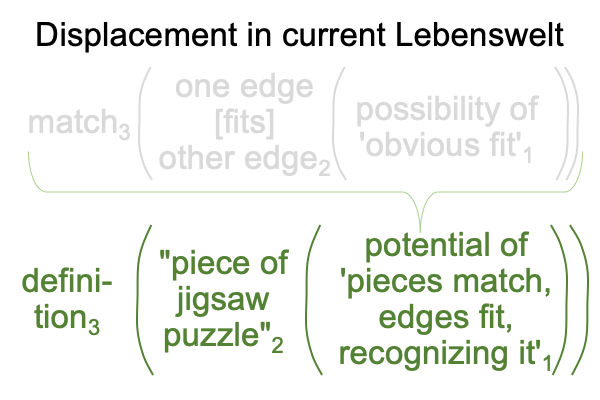

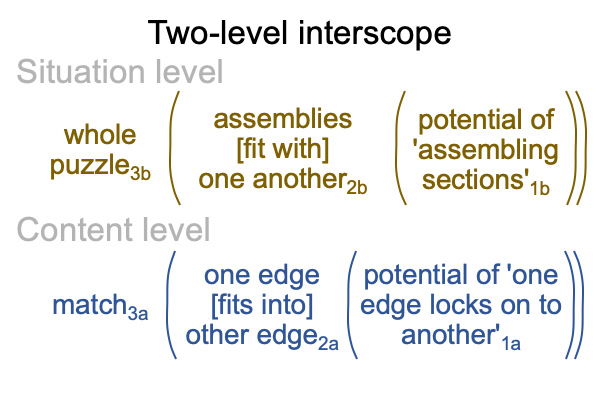

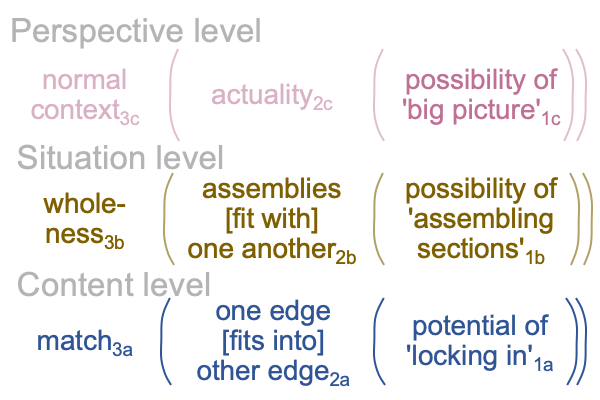

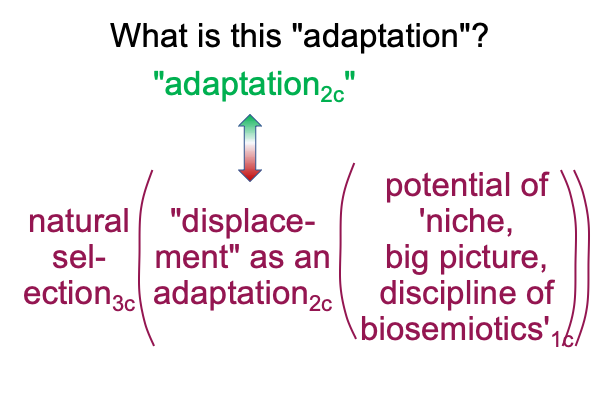

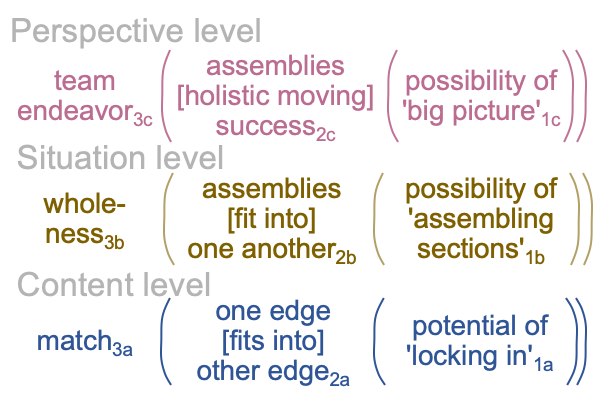

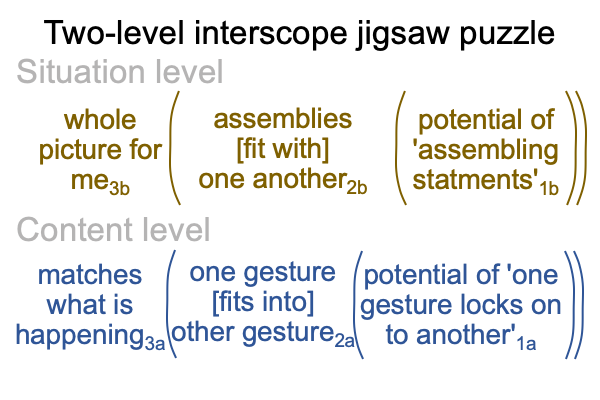

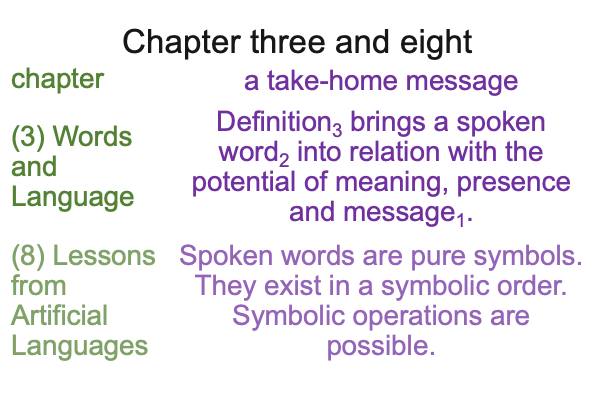

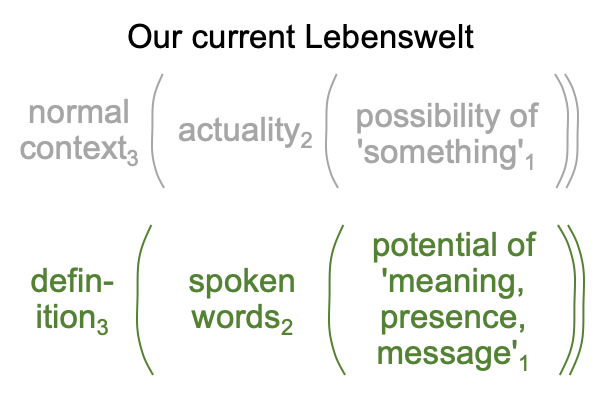

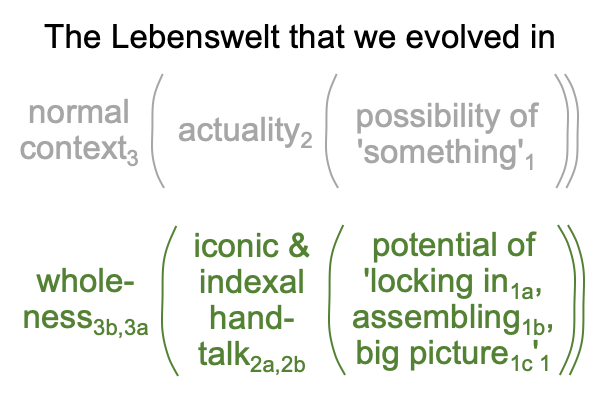

0009 A Primer on the Category-Based Nested Form and A Primer on Sensible and Social Construction (by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues) should assist in comprehending the triadic relation diagrammed above. The triadic normal context of a match3 brings a dyadic actuality2, {one edge [fits] another edge}2, into relation with the monadic potential that ‘the fit will be intuitively obvious’1.

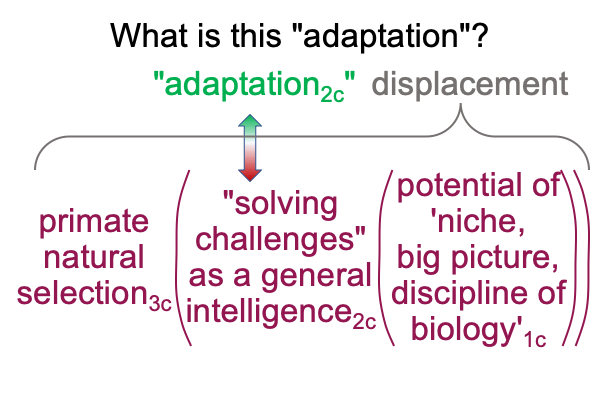

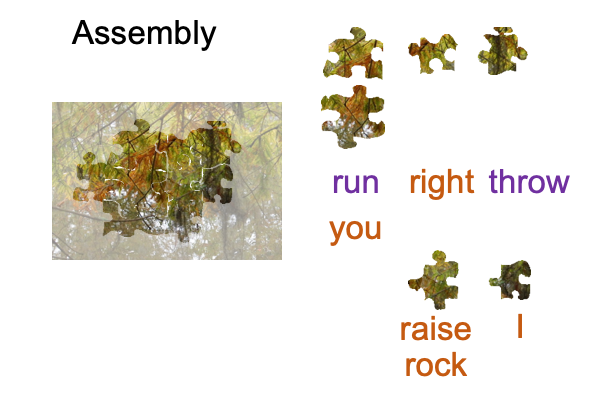

0010 The category-based nested form is not the only triadic relation in play.

In terms of the natural sign-typology of Charles Peirce, the image is an icon. The edge-shape is an index.

0011 An icon is a natural sign-relation, whose sign-object is determined on the basis of similarity, imagery and other characteristics of firstness. Firstness is a category, corresponding to the monadic realm of possibility.

0012 An index is a natural sign-relation, whose sign-object is determined on the basis of contiguity, cause and effect, action-reaction and other characteristics of secondness. Secondness is a category, corresponding to the dyadic realm of actuality. Secondness contains two contiguous real elements. For nomenclature, the contiguity is placed in brackets. For example, for Aristotle’s hylomorphe, the two real elements are matter and form. The contiguity? I propose to use the word, “substance”. So, for Aristotle, a thing is matter [substance] form.

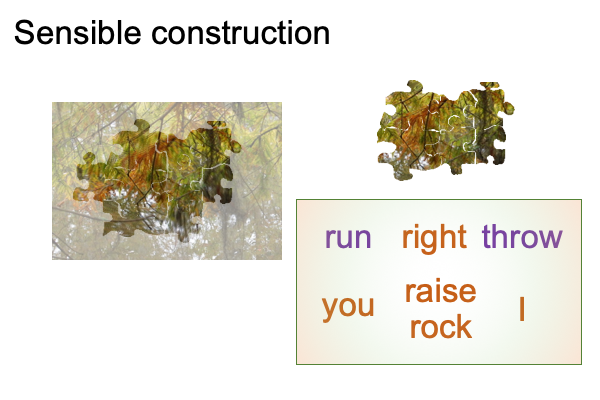

0013 So, jigsaw puzzles contain pieces that are icons and indexes.

What about the third type of natural sign?

What about the symbol?

Well, if I follow the pattern for icons and index, the symbol is a sign-relation whose sign-object is determined on the basis of what?… not imagery… not indications… how about the fact that each symbol has to be different from any other symbol. Of course, nobody thinks about that when they use the word, “symbol”. Indeed, this attribute sounds positively ridiculous, even though correct.

0014 For example, the moon offers an image of a nearby planetesimal. The moon points to the sun, because its every changing face is due to sunlight striking its surface. Then, I ask, “How can the moon be a symbol, if it is the only symbol and there aren’t any other moons?”

To which, I say to myself, “Well, why don’t I go out one night, away from the city, away from the camp, and sit myself down in its pale light and ask it, ‘What on Earth do you symbolize?”

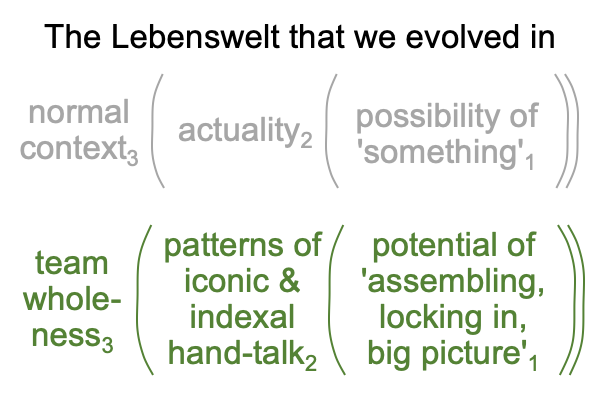

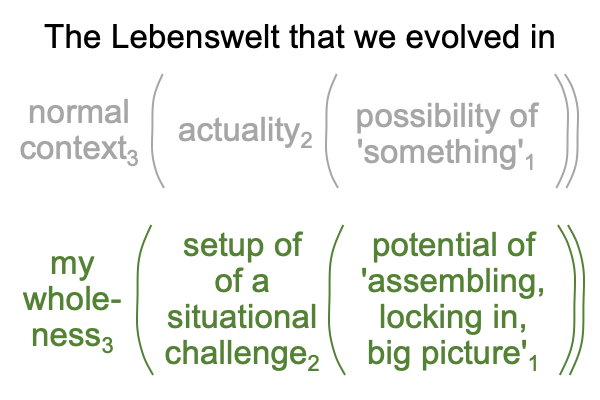

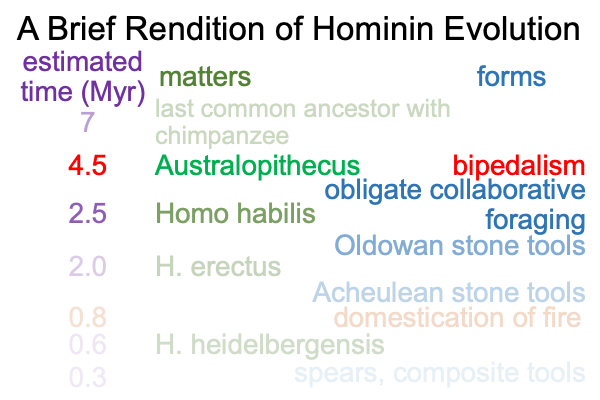

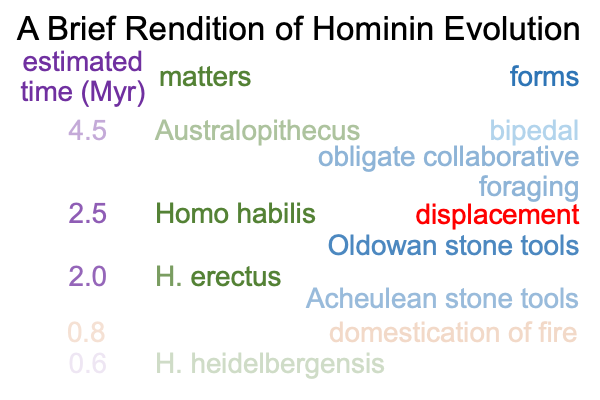

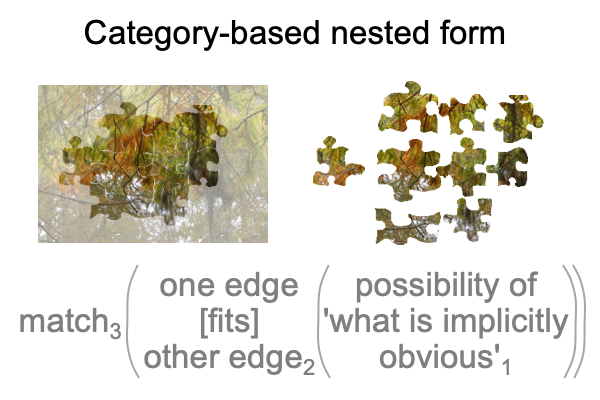

0015 Strangely, this is not what any of our ancestors in the Lebenswelt that we evolved in could ever ask.

Why?

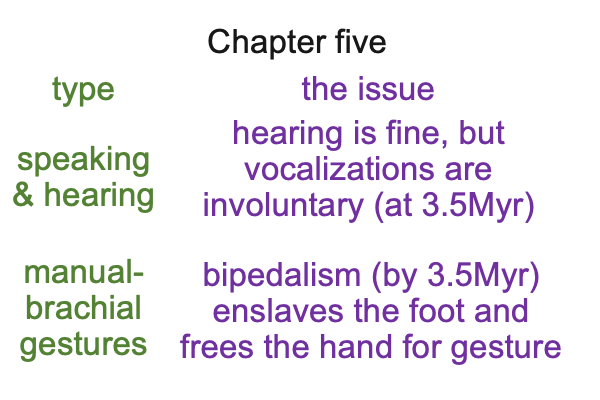

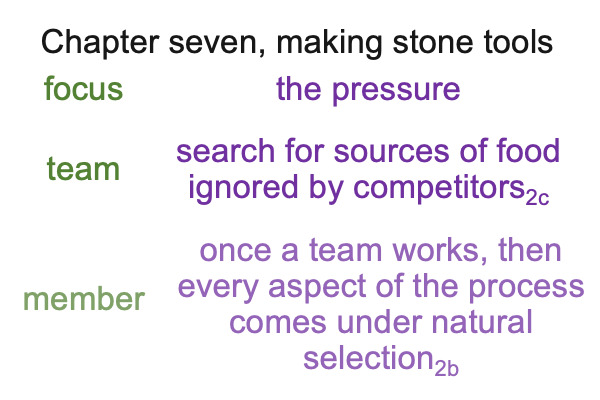

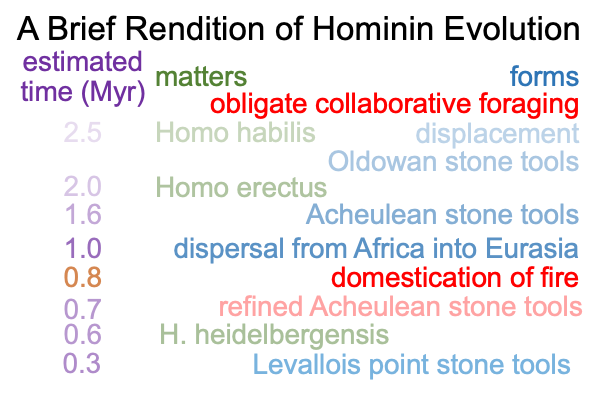

The Homo genus practices hand talk, then adds speech to hand talk, then ends up with speech-alone talk.

Hand talk belongs to the Lebenswelt that we evolved in.

Hand talk words image or point to their referents.

They serve as images and icons.

So, where is the symbol in hand talk?