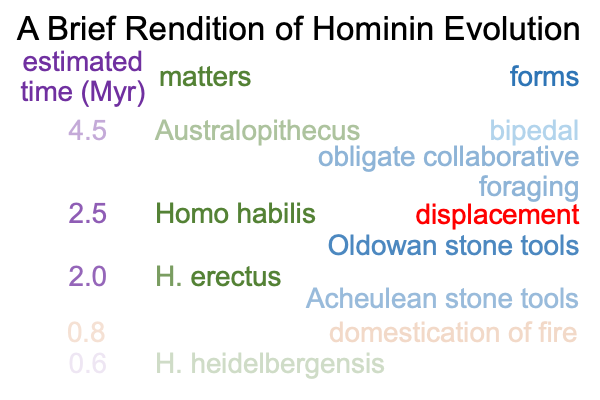

0074 In chapter six, Mithen discusses iconic and arbitrary spoken words. Displacement is accounted for by iconic spoken words. But, arbitrary spoken words can proliferate and inhibit the success of iconic spoken words. Consequently, Mithen suggests that the evolution of language is postponed until after the domestication of fire.

0075 So, what is the problem?

Displacement is the ability to indicate a referent, without the referent actually being present. Iconic and indexal natural signs involve displacement. The adaptation of displacement probably takes place before or during the evolution of the Homo genus.

0076 Why do I say this?

As far as I can see, obligate collaborative foraging requires word-based communication, that is, displacement. If the iconic word-sound route is too slow, then why not exploit another generator of signs that is under voluntary control (that is, manual-brachial gestures)?

0077 What about stone-tools?

In chapter seven, stone-tool technology is discussed. Oldowan tools appear in the fossil record either before or around the same time as the first species in the human genus: Homo habilis.

To me, this indicates the relevance of Tomasello’s hypothesis of obligatory collaborative foraging and Gamble, Gowlett and Dunbar’s concept of the social circle of the team. It also indicates that displacement as a cognitive adaptation has already taken place (or takes place with the emergence of the Homo genus).

0075 To recall, Mithen rules out the gestural origin of language in chapter four. He asks (more or less), “How does one account for the long and gradual modification of the call-system of vocalization if language evolves in the milieu of manual-brachial gesture?”

And, how can an ape figure out whether an iconic gesture pictures this or that referent?

0076 Of course, a biosemiotician can turn these questions around and ask how involuntary calls, such as the vervet alarm-call business, can adapt to displacement, when the purpose of calls is to indicate the presence of the referent. All vocalizations in the mammalian world seem oriented to call attention to the presence of a referent, rather than making a (not present) referent present as a sign-object in a sign-relation.

0077 Displacement is the foundation of language. Displacement is a sign-process that makes a referent present as a sign-object, even when the referent is not present. This is precisely what spoken words do. In Mithen’s account, displacement and speech co-evolve due to a process called “synaesthesia”. “Syn” means “across”. “Aesthesia” means senses (the basis for aesthetics). So, “synaesthesia” involves sensory cross-over.

For Mithen, the crossover is from vision, smell, taste and touch to hearing.

The idea has a respectable pedigree.

But, this examiner rejects the application of synaesthesia to this period of human evolution on the following basis.

0078 Once the inquirer considers Michael Tomasello’s proposal of obligatory collaborative foraging as the cultural adaptation dominating the second period of hominin evolution, from the emergence of bipedalism to the domestication of fire, then the evolution of proto-linguistic hand talk does not seem so far fetched. The manual-brachial gesture-wordserves as an iconic and indexal sign-relation, accounting for displacement. The social circle of the team demands that word-gestures are constrained and easily recognizable. This accounts for why words can literally be compared to pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

0079 Say that again.

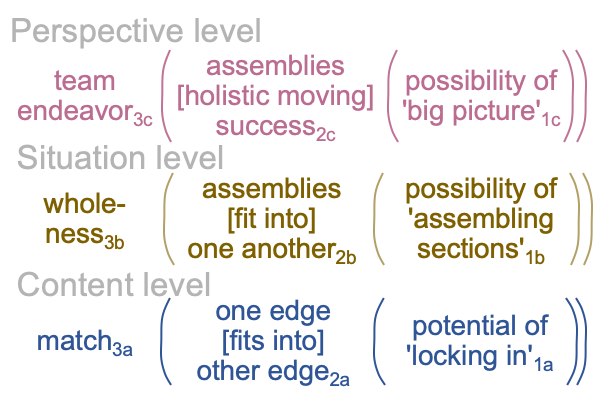

Comments on Clive Gamble, John Gowlett and Robin Dunbar’s book (2014) Thinking Big (available at smashwords and other e-book venues) allows to inquirer to claim that the social circle of the team (15) associates with obligatory collaborative foraging. Then, team endeavor3c serves as the normal context for the perspective level, which accounts for displacement. Without a perspective level, displacement does not occur, because displacement belongs to the potential1c of the whole picture3b.

0080 Here is a diagram of the three-level interscope.

On the content level, in the normal context of matching3a, the way that one edge of a jigsaw puzzle piece fits into the edge of another piece2a emerges from (and situates) the potential of ‘locking in’1a.

On the situation level, the normal context of the whole puzzle3b brings the way that one assembly of pieces fits into another assembly of pieces2b into relation with the possibility of ‘assembling sections of the jigsaw puzzle’1b.

On the perspective level, the normal context of a team endeavor3c brings the vision captured in the jigsaw puzzle2c into relation with the possibility of ‘a big picture’1c.

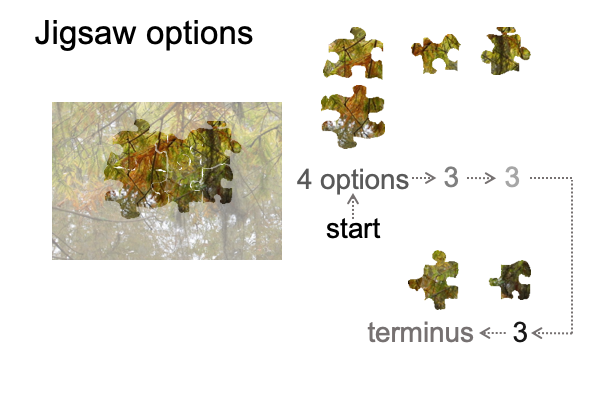

0081 Of course, this figure confounds manual-brachial word-gestures and pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. It is as if gesture-words are symbolic, just enough, to not only distinguish one from another, but to provide a certain two-dimensional shape. So, the shape of one word-gesture will habitually lock into the shape of other gesture-words, in the same way that one piece of a jigsaw puzzle locks into a limited number of other pieces (typically, four).

In short, by taking the metaphor that a word is like a piece in a jigsaw puzzle literally, one arrives at a picture of how symbolic operations (or grammatical conventions) might operate in team proto-languages.

0082 Here is a picture of how the literal metaphor limits the number of options for each step of a sequential statement.

0083 Each of the pieces is iconic and indexal, in so far as it is a natural sign that images or indicates its referent (even when the referent is not present). Also, each of the pieces is arbitrary (or symbolic) in so far as team conventions make sure that each gestural-word is distinct and easily recognizable. This characteristic defines symbols. In any symbolic order, each symbol is distinct from all other symbols, according to habit, convention, tradition and so on.

Symbolic operations connect the pieces together.