Looking at Ian Hodder’s Book (2018) “Where Are We Heading?” (Part 6 of 15)

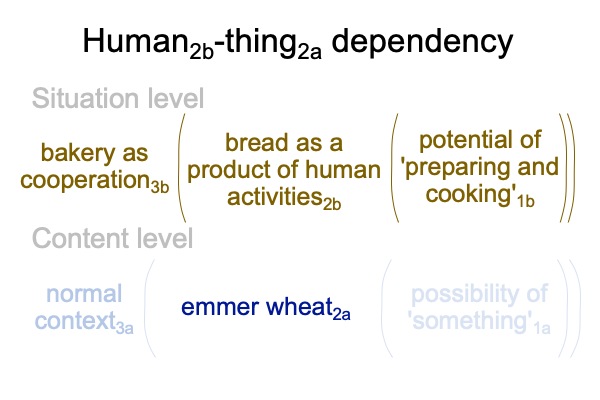

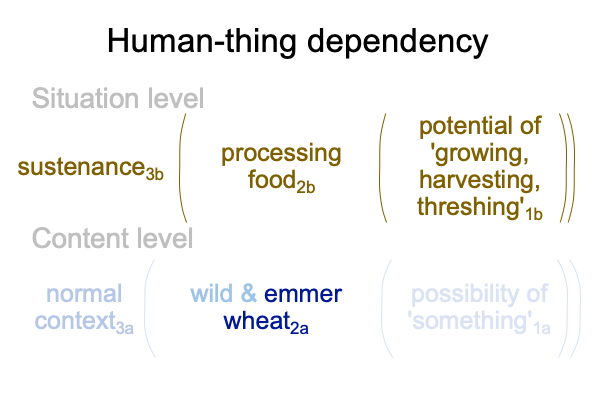

0045 Here is the application of Hodder’s sensible theory with respect to emmer wheat2a as a thing2a. In human-thing dependency, processing food2b virtually situates emmer wheat2a. Humans2b depend on things2a. I call this H2b-T2adependence.

0046 Chapters four (“Humans and Things”), five (“Webs of Dependencies”), six (“The Generation of Change”) and seven (“Path Dependency and Two Forms of Dependencies”) fill in details.

0047 For example, the potential of ‘the growing, harvesting and threshing’1b of emmer wheat2a designates a human-thing (HT) dependency.

One could say that the biological adaptations occurring in the wheat designate a thing-human (TH) dependency. But, a more obvious designation of thing-human dependency are the tools that were invented in order accomplish specific tasks, including baskets for holding seeds and clay pots for cooking mush. These tool-things would not exist were it not for humans.

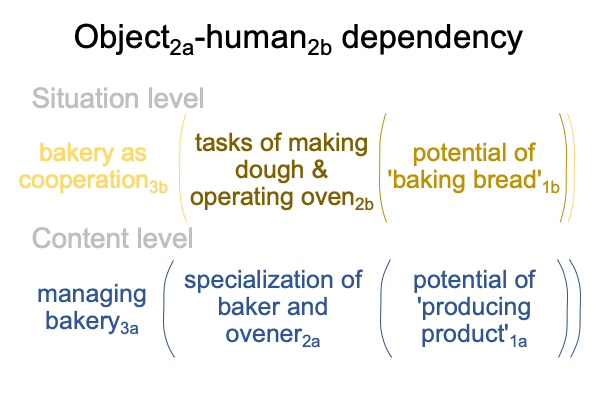

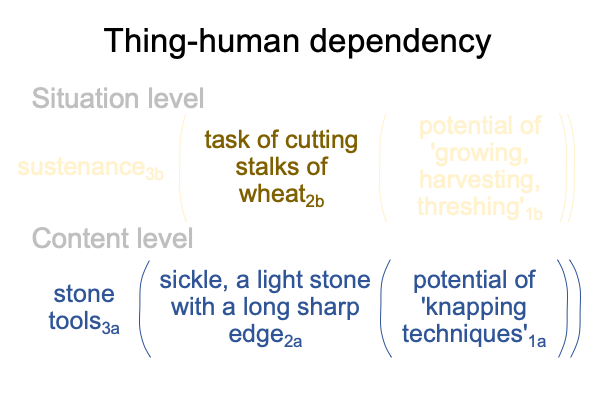

0048 For example, cutting grass stalks is one of the tasks in processing food2b from emmer wheat2a. This task2b situates a content-level nested form in such a manner as to project an artifact2a into the slot for thing2a. That artifact is a stone sickle2a. Some things2a depend on humans2b. I call this T2a-H2b dependence.

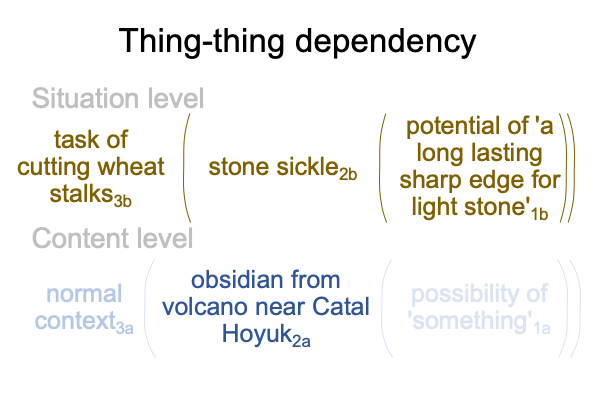

0049 On top of that, there is a subsidiary of H2b-T2a dependence that associates to the desirability of the tool1b for its particular task2b. Certain tools work better than others. A stone sickle made of obsidian is better than one made of granite. The obsidian from a volcano near Catal Hoyuk2a makes great tools, not only sickles, but knives and arrowheads. This obsidian is found throughout the ancient Near East, showing evidence for down-the-line trading during the early Neolithic.

0050 I call this T2b-T2a dependency.

0051 Hodder proposes one more dependency. To me, this dependency is unlike the three types covered so far. But, Hodder does not see that this additional dependency is unlike the rest. I wonder whether there is evidence of it to be found in the archaeological site of Catal Hoyuk.