0129 Back to that law of economics that falls into the lap of a Buddhist economist, while playing with Zizek’s configuration.

Does Buddhism or does Zizek’s configuration account for this law?

Don’t ask me.

I am busy preparing a scenario to distract the reader from the question.

0130 In our current Lebenswelt… I have to throw in the German term for “living world” to show that this is serious… if I fixate, not so much on making high-quality clay pots, but in manufacturing so many clay pots as to attain wealth and power, then I hire a machine or a robot to accomplish the task without illusions… er… with singular intent.

On the content level, the contiguity between acquisition2a and the exercise of order2a is mechanically specified, using scientific models for clay and angular momentum.

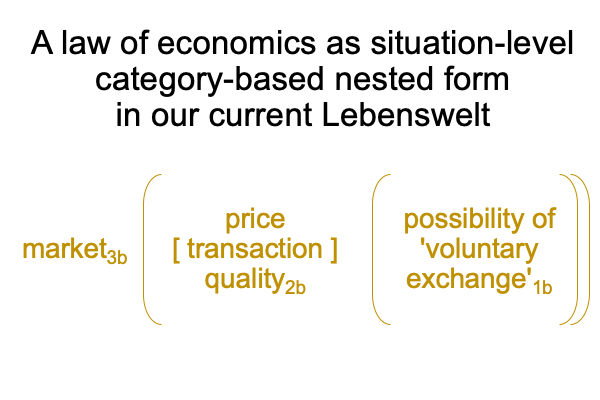

On the situation level, the real clay pots that my corporation manufactures with no imaginary components2a command a certain price2b, due to demand in a market3b that operates on voluntary exchange1b. Quality2b can be defined as the price2b at which a transaction takes place. And so, I may begin my calculations, comparing quality2b to the actual production costs of the specified product2a. The larger the difference between quality2b and production costs2a, the closer I get to wealth and power for each transaction.

0131 Hmmm. Does this sound Buddhist in any way?

Or am I missing something?

0132 I guess that I am missing the trade-off within the transaction2b.

Also, I am missing the oneness of jouissance and the potential of voluntary exchange1b.

0133 That brings me to the Lebenswelt that we evolved in. Our current Lebenswelt is not the same as the Lebenswelt that we evolved in. The conclusion is obvious after reading Comments on Michael Tomasello’s Arc of Inquiry (1999-2019) by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues. Professor Michael Tomasello worked for many years at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Parts of the commentary appear in Razie Mah’s blogs for January through March, 2024.

0134 Jouissance1b is about desire, under conditions where trade-offs are real. Desire is hidden within the possibility of ‘voluntary exchange’1b. My desire is not only for quality. I ask, “Will it satisfy my demands?” I want a good clay pot for making tea. I also am interested in a “reasonable” price. So, desire pertains to the objet a, which is composed of the matter of price and the form of quality. [Transaction] is the contiguity between price2b and quality2b.

[Transaction] is like a substance that makes price2b and quality2b real.

[Transaction] is a situation-level petit objet a.

0135 Where does the jouissance of voluntary exchange1b come from?

Uh oh, am I going to talk about human evolution?

Is this type of jouissance a human adaptation?

0136 Michael Tomasello offers an insight. Once our distant ancestors are bipedal, in the ecology of mixed forest and savannah, individuals find that they cannot walk, bring the kids, and forage for the needed calories. So, rather than individually foraging, they adopt collaborative foraging. They start working in teams, in order to take advantage of opportunities that are not available to individuals.

For example, after a big rain in Africa, edible mushrooms sprout on the edges of certain dung heaps. These are not available to an individual Homo erectus. Why? Being out in the open is dangerous and, after a dozen or so mushrooms, the interloper has eaten enough. Abundance is available to a team carrying crudely manufactured baskets. A team, numbering 15, employs a certain degree of labor specialization, such as lookout, gatherer and organizer. That helps. In short order, the team gathers enough to feed… not only the team… but the entire band. The band numbers 50.

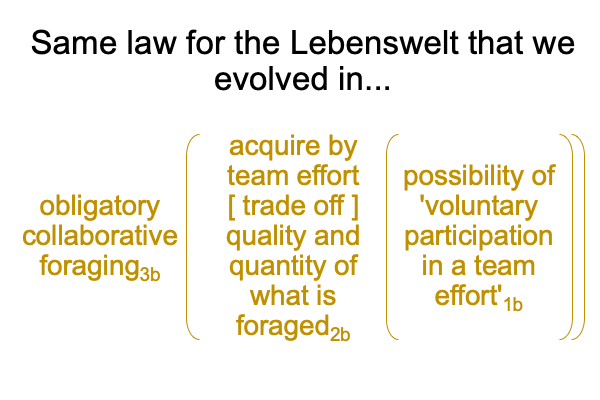

0137 In this example, pertinent to over 600,000 years ago, obligatory collaborative foraging3b is the normal context for the team. Voluntary participation reflects jouissance1b, as the potential of ‘situational truth and synthesis’. The truth is that mushrooms sprout at certain locations on the savannah after a big rain. The synthesis is that every member of the team has acquired knowledge about these mushrooms, which are edible and which should be avoided, plus habits that pertain to keeping a lookout for predators and the ability to throw a rock accurately, plus a certain know-how that keeps everyone on task and tracks how full the baskets get.

0138 The actuality involves a [trade-off]. Acquiring mushrooms requires effort and risk. The quantity and quality of the mushrooms is the reward.

0139 Yes, this looks very much like a transaction. It also plays out as an implicit abstraction. This is how foraging happens in the Lebenswelt that we evolved in. The above figure portrays a species-specific adaptation.

In our current Lebenswelt, the corresponding “economic law” is codified as an explicit abstraction and formulated into some sort of equation. In this regard, the Buddhist has a point. The codified version is like an illusion. The illusion is a trap filled with apparently spiritual beings that say, “This is the objet a that you are looking for.” Are you looking for price? Or, are you more focused on quality?

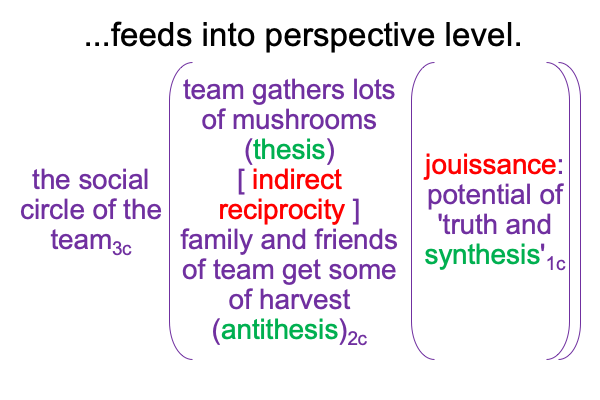

0140 That is not all. The dramatic events of living in the wild are missing. In the Lebenswelt that we evolved in,situation-level team activity is contextualized by the social-circle of the team3c. Plus, the team is one3c, within a panoply of social circles. Social circles characterize hominin society. In this regard, see Comments on Clive Gamble, John Gowlett and Robin Dunbar’s Book (2014) Thinking Big (by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues).

Can I go so far as to say the following?

The mushrooms growing around steaming wet turds2a, the gathering of the mushrooms by a team on the open savannah2b and the sharing of those mushrooms with friends and family2c work in tandem. One flows into the other in a virtual category-based nested form. The flow illuminates an evolutionarily deep expression of Zizek’s configuration, as shown in the following figure.

0141 Here is a picture of the perspective-level that virtually contextualizes the situation-level of obligatory collaborative foraging3b.

0142 Notice, that the contiguity is not [wealth and power]. It is [indirect reciprocity], the expectation that, in giving now, one will later receive a return. The [transaction] of our current Lebenswelt supports [direct reciprocity]2c, the expectation that I give now and immediately get something in return.

[Direct reciprocity]2c?

Doesn’t that sound like [wealth and power]2c?

Nothing is given without an expectation of return?

Nevertheless, in our current Lebenswelt, [indirect reciprocity]2c offers an alternate label for [wealth and power]2c. And, Christ3c raises the ante with [altruism]2c, which is giving with no expectation of return.

Surely, these are illusions.

But, they are also adaptations.

0143 Does this explain why Lacan is not a Buddhist?