0015 In comedies and in tragedies, the audience always knows something that the characters on stage do not. I do not know whether Tabaczek’s enormous and grueling efforts are funny or futile in the eyes of God. But no matter how God views the author’s long and arduous studies, I know this.

Tabaczek does not employ, analyze or justify the distinction between philosophers of science (who are concerned about models) and analytical metaphysicians (who are concerned about noumena).

Tabaczek does analyze and review a massive amount of academic material in his effort to show that a revised “neo-Aristotelianism” is available to contemporary philosophers of science. Aristotle’s four causes should assist philosophers of science who wrestle with the question of emergence. His academic work is diligent and earnest.

0016 I see what Tabaczek is trying to do.

I conclude that his demonstration will inevitably fail.

0017 How so?

My answer relies on Comments on Jacques Maritain’s Book (1935) Natural Philosophy, as well as the commentaries listed in the series, Phenomenology and the Positivist Intellect. These are available at smashwords and other e-book venues.

The following argument complements Tabaczek’s brief history of causality from the middle ages to the present (sections 1.3 to 1.5).

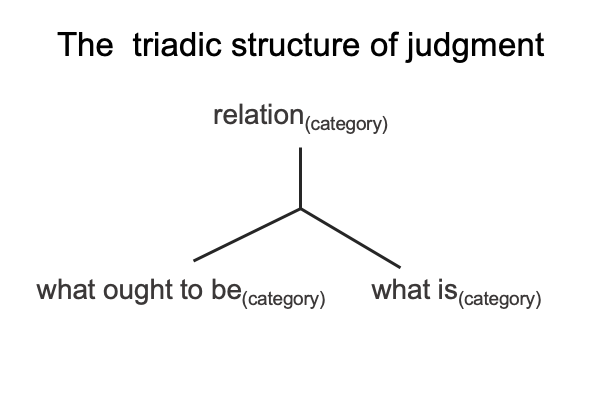

0018 I start with the question, “What is judgment?”

A judgment is a triadic relation consisting of three elements: relation, what is and what ought to be. When each of these elements is assigned to one of Peirce’s categories, then the judgment becomes actionable. Actionable judgments “unfold” into category-based nested forms.

Here is a picture of the general form of judgment.

In judgment, a relation (category) brings what ought to be (category) into relation with what is (category).

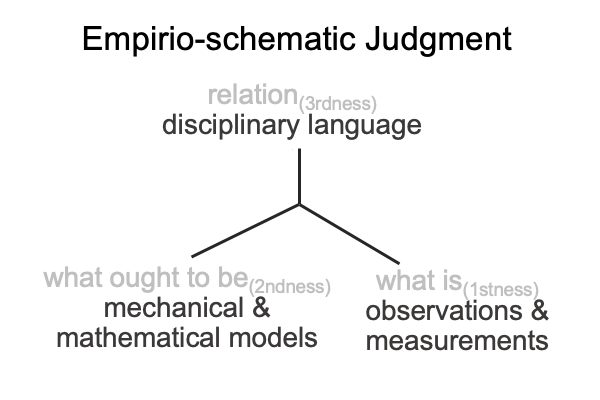

0019 I already stated the empirio-schematic judgment. Let me say it again. Disciplinary language (relation, thirdness) brings mathematical and mechanical models (what ought to be, secondness) into relation with observations and measurements of phenomena (what is, firstness).

Here is a picture.

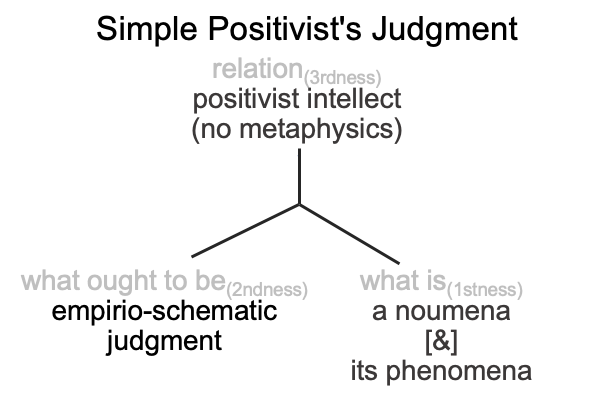

0020 The empirio-schematic judgment occupies the slot for what ought to be for the Positivist’s judgment. The fact that the Positivist’s judgment contains the empirio-schematic judgment is confusing. Plus, the positivist intellect has a rule saying, “Metaphysics is not allowed.”

Here is a simplified picture.

0021 Simplified?

The Positivist’s judgment is initially formulated, in the early 1700s, as provincial mechanical philosophers (in northern Protestant Europe) reject the universal Latin-Age scholastics (in all of Europe, but mainly southern and Catholic Europe). These mechanical philosophers aim to narrow inquiry to the observations and measurements of phenomena.

The relation in the Positivist’s judgment is the positivist intellect, who enforces only one rule. Metaphysics is not allowed. This rule dooms Tabaczek’s quest from the start. Aristotle’s four causes allow the inquirer to understand the noumenon. Modern science in the Age of Ideas wants to mathematically and mechanically model observations and measurements of phenomena.

0022 The [and], the contiguity between a noumenon and its phenomena, becomes a point of contention. The argument ends up in a truce, of sorts. Casual readers of Kant come up with a slogan to replace the [and], at least for advocates of science. The substitute is [cannot be objectified as]. A noumenon [cannot be objectified as] its phenomena.

0023 To me, the what-is-ness of a noumenon [cannot be objectified as] its phenomena dooms Tabaczek’s quest.

However, Tabaczek is rewarded his doctorate and his impossible project is written up and published by University of Notre Dame Press.

What does this indicate?

Is the Positivist’s judgment in trouble?