0037 At around the age of nine months, sensible construction comes to life.

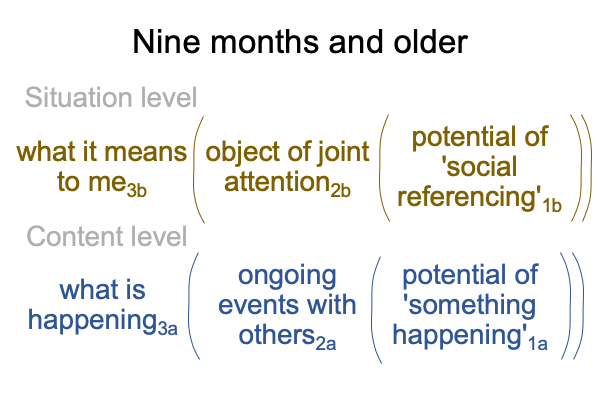

On the content level, the normal context of what is happening3a brings the actuality of ongoing events with others2a into relation with the potential of ‘something happening’1a.

On the situation level, the normal context of what it means to me3b brings the actuality of the object of attention2b into relation with the potential of ‘social referencing’1b.

Tomasello provides details. For example, three types of joint attention emerge in sequence. First, check the attention of others. Next, follow the attention of others. Then, direct the attention of others.

0038 Tomasello aims for a theoretical account that addresses two questions.

First, why do all joint attentional skills manifest in a particular pattern?

Second, why do they manifest starting at nine months of age?

0039 Tomasello proposes that infants start to engage in joint attention when they begin to “understand” others as intentional agents like the self.

Is understanding (that is, comprehension) necessary?

Or does competence in the above sensible construction suffice?

Infants pay attention to the actions of others2a and situate the implied social reference1b with an object of joint attention2b.

Does this classify as sociogenesis?

Yes, it does.

0040 Plus, the above sensible construction does not depend on an explicit abstraction of the self as a participant.

Instead, the sensible construction generates the self as a participant3b within joint action2b.

0041 The sensible construction pictured above is experienced holistically.

Social and cognitive scientists can only observe and measure facets of this whole relation. So, they build models that explicitly abstract one of the elements. This foregrounds the abstracted element and backgrounds the others. For example, experiments may be designed to foreground the self3b, with the result that objects of joint attention2b may be classified as “like me” and “not like me”.

Are social and cognitive scientists observing what their models are asking them to look for?

Uh oh. Is this another tautology (point 0017)?

I wonder whether Tomasello’s research program may be an exercise in social construction, because social constructions often have a tautological character, where the perspective level refers back to the content level, and the situation level takes on a vague or an unsettled tone.

0042 I can say that models of newborns and infant psychology support a hypothesis that human ontogeny (body and behavioral development) is phenotypic. Phenotypes and adaptations not the same. But, they constitute one entity. Adaptation and phenotype coincide in that entity. But, they are not the same

So, a question arises about the potential that an adaptation exploits or avoids. That niche is the potential of something independent of the adapting species.

For human ontogeny2b, not as a phenotype, but as its corresponding adaptation2b, the niche1b, must be… hmmm… the potential of culture, where culture is something independent of the adapting species2a.

0043 To me, this recalls the awkwardness of points 0014 through 0019.

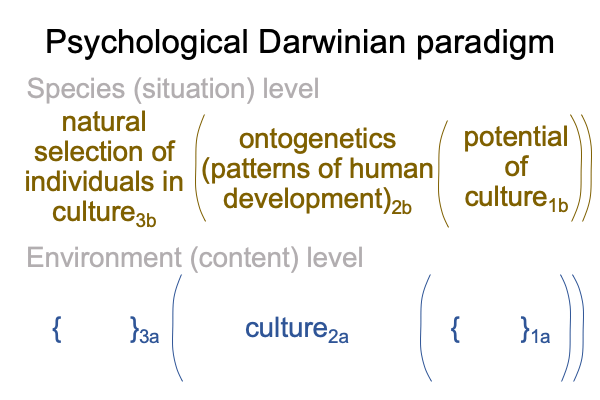

Here is a diagram of the resulting Darwinian paradigm.

0044 Tomasello (and other cognitive psychologists) construct Darwinian paradigms that locate culture2a as the actuality independent of the adapting species2a in order to identify phenotypic traits as adaptations2b. The adapting species are children3b, which the above paradigm labels as “individuals within culture”3b.

The normal context of natural selection of individuals within culture3b brings the actuality of phenotypical patterns of human development2b into relation with the potential1b of an actuality independent of the adapting species2a.

What is that independent actuality2a?

Culture2a.