0070 Here is a key distinction that develops as early as three million years ago.

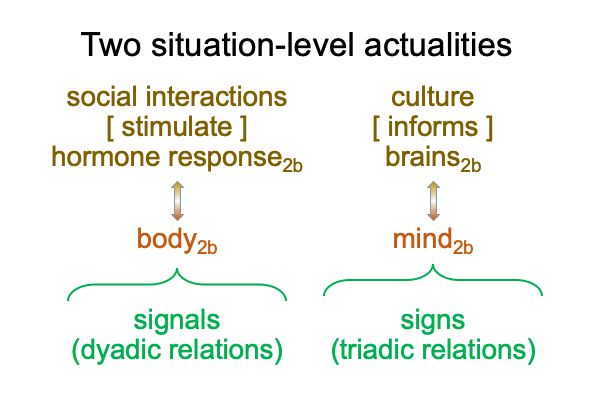

These situation-level actualities fit into a three-level interscope that (more or less) depicts the relational character of the author’s theoretical approach.

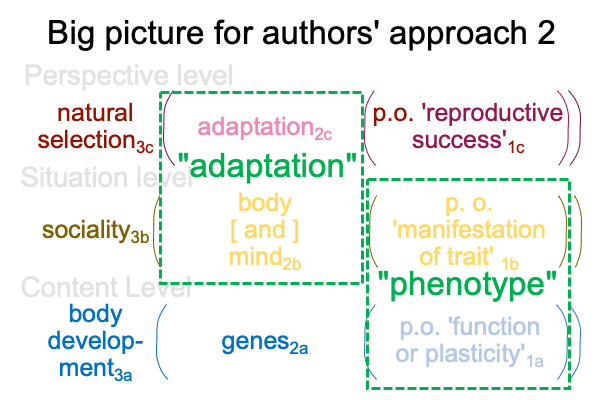

0071 For gene-culture co-evolution, genes2a associate with “phenotype” and culture2b associates to “adaptation”. “Adaptation” and “phenotype” are big category-crossing words.

0072 The transition from (one branch of the) southern apes to the Homo genus occurs by 1.5Myr (million of years ago). This time serves as the snapshot for chapter four, concerning early humans.

0073 Clearly, the authors are worried about how we gain voluntary control of our vocal apparatus in order to speak. They do not imagine that the stage is set for the routinization of manual-brachial gestures during team activities.

Why is routinization so important?

As the gestures of hand talk become more distinct from one another, they start to form a system of differences. According to Ferdinand de Saussure, language consists in two arbitrarily related systems of differences, parole (speech) and langue(processed sign-objects). The relation is arbitrary for speech, but not for hand talk. Hand talk pictures and points to its referents.

In short, language evolves in the milieu of hand talk, not speech talk.

0074 But, everyone speaks today. So what gives?

Well, the answer to that comes much, much later.

0075 Instead of really confronting how language could have evolved, the authors assume that all languages are spoken. So, they tell a story about the mouth.

In order to get linguistic speech, the mouth and throat must come under voluntary neural control.

The story is about a mother chewing food and spitting it into the mouth of her weaning child. Certainly, that cultural behavior encourages adaptation towards voluntary neural control of the mouth and throat. But, where does a need for a functional vocabulary come into play?

0076 In the same story, the authors discuss Acheulean stone tools (mentioned earlier in point 0065) and imagine a whole team of hominins joining to appear as a single very large animal in order to approach and scavenge a carcass. Now, that is teamwork! Manual-brachial gestures are crucial for this type of job. The more readily that each specific gesture is interpreted, the better off everyone is.

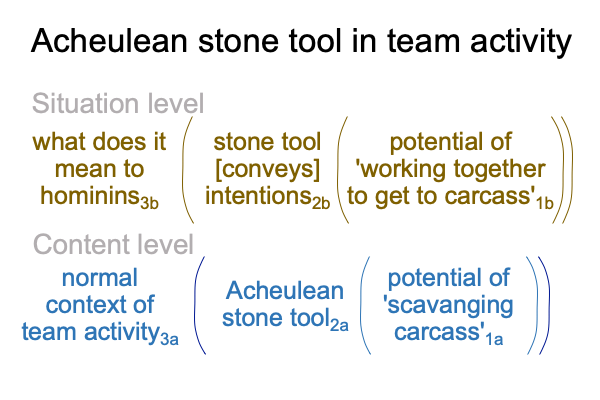

0077 Here is a two-level interscope that fits this portion of the story.

0078 The Acheulean stone tool3a is a sign-vehicle. The sign-object is the dyad, stone tool [conveys] intention2b. The Acheulean stone tool is like a big tooth, capable of slicing meat off carcasses and crushing the bones to get the fatty marrow. In hand talk, I can picture or point to the stone tool, but I cannot picture or point to the sign-object, even though I know that stone tool [conveys] intention. All the participants have the sign-object in mind, but no one can talk about that in hand talk. Even more important, each participant holds a similar normal context3b, where the team activity of scavenging is significant3b, and potential1b, where working together must occur in order to accomplish the task1b.

Manual-brachial gestures2b are the way that hominins talk in team activities2c. Once gestures are routinized, symbolic processing characteristic of grammar may evolve.

0079 Hand talk does not allow the participants to “name” the sign-object and sign-interpretant. Hand talk images and indicates a sign-vehicle. Everyone recognizes the sign-vehicle, then implicitly abstracts a sign-object (that cannot be pictured or pointed to). That implicit abstraction is the sign-interpretant.

The Homo genus gets better and better at scavenging and hunting.

The Homo genus gets better and better at reading signs.