Looking at Gustavo Caetano-Anolles’ Chapter (2024) “Evolution of Biomolecular Communication” (Part 1 of 10)

0324 The text before me is chapter ten in Pathways to the Origin and Evolution of Meanings in the Universe (2024, edited by Alexei Sharov and George E. Mikhailovsky, pages 217-243). The author hails from the Evolutionary Bioinformatics Laboratory at the Department of Crop Sciences and Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, at the University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois, USA. The author and editors have permission to use and reprint this commentary.

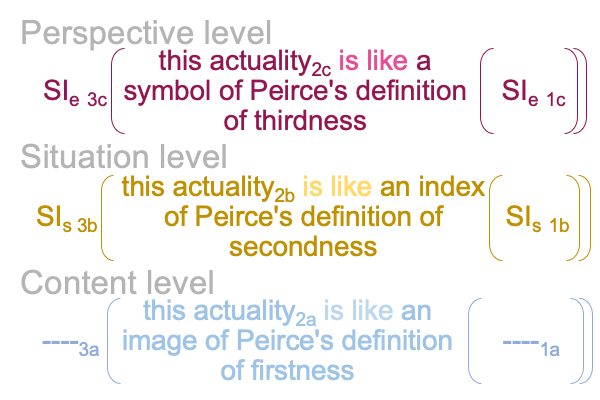

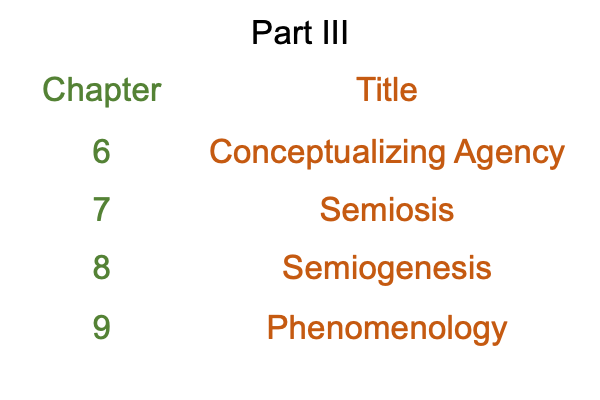

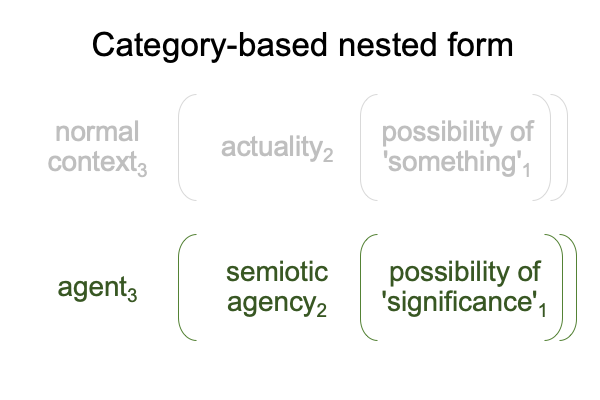

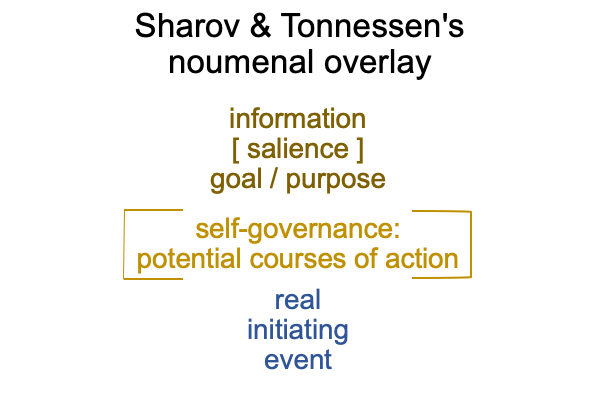

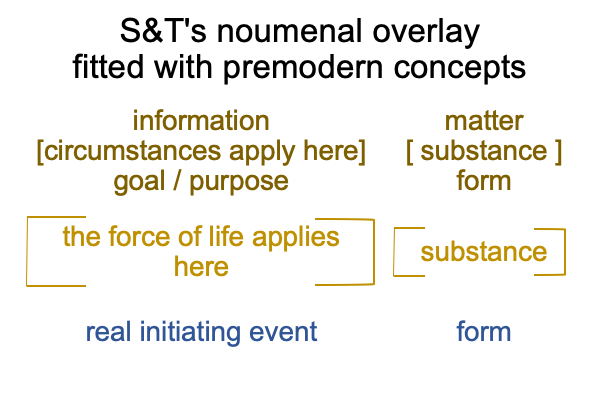

From prior examinations, I propose that Alexei Sharov’s and Morten Tonnessen’s 2021 book, Semiotic Agency, formulates a noumenal overlay for the diverse field of biosemiotics. All manifestations of semiotic agency are unique. Each is a subject of inquiry on its own. Yet, they have one relational structure in common. Here is a picture of that dyadic actuality.

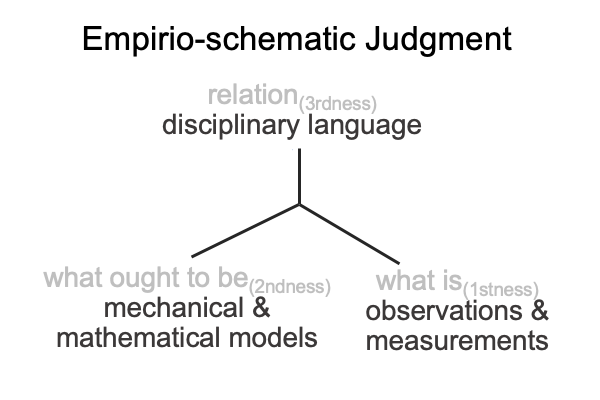

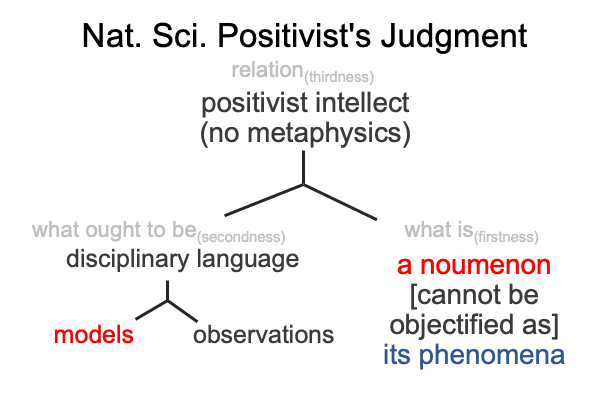

0325 Biosemiotics is not divorced from science. Scientists observe and measure phenomena, then build models based on those observations and measurements. The real elements in the above figure support phenomena. The contiguities (in brackets) call for models.

0326 So, what about communication mediated by biomolecules?

0327 In the introduction (section 10.1), the author reminds the reader of two premodern views of biological behaviorsand how they change over time. One is the force of life (in French, le pouvoir de vie), which tends to increase complexity. The other is the influence of circumstances (in French, l’influence des circonstances), which tends to select for… um… survivors.

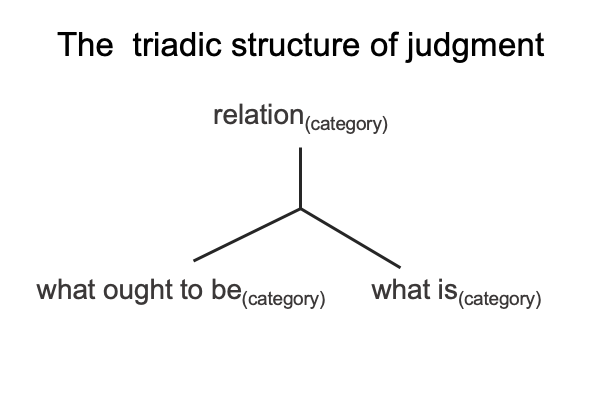

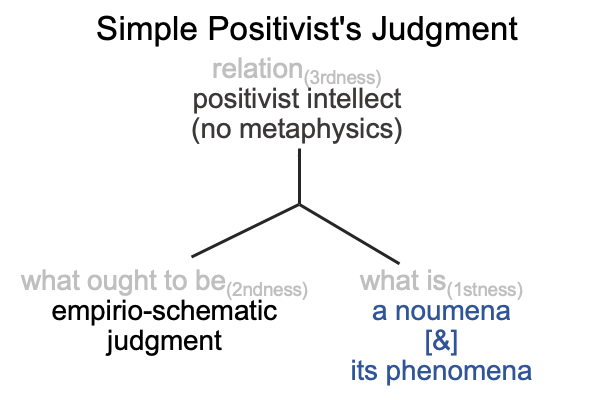

These premodern views fit nicely into the contiguities in the above relational structure. Each dyad can be compared to Aristotle’s hylomorphe of matter [substance] form, allowing the following comparison.

0328 The force of life tends towards the many.

The influence of circumstances tends toward the few.. or rather… one goal.

Surely, my assignments are confusing, because the force of life is singular and circumstances tend to vary. Also, real initiating events can vary. But, goals tend to rule out alternatives.

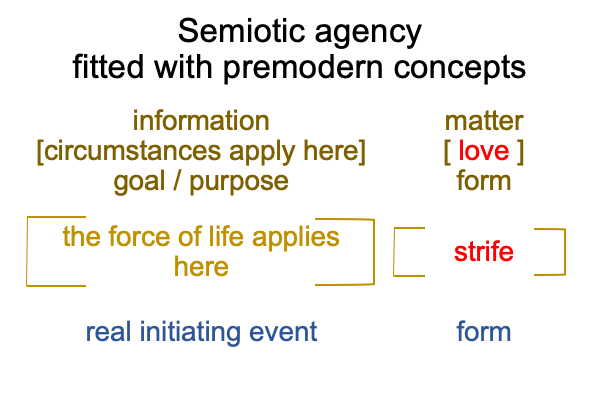

0329 The author then draws upon a recently translated papyrus scroll, attributed to Empedocles. Empedocles speaks of two opposing forces, one capable of growing things together from the many and one capable of growing things apart. The former is labeled, “love”, the latter, “strife”.

0330 I wonder, “How does this ancient distinction fit into the schema pictured above?”

Here is my suggestion.

I have a 50:50 chance of being correct.

0331 Strife goes with the force of life, tending towards the many. Love goes with the influence of circumstances and tends towards a singular goal.

Both are substances and reflect (however distantly) Aristotle’s exemplar: matter [substance] form.

In the above figure, the real initiating event is like an form that conjures matter (information). At the same time, that matter (information) substantiates another form (goal). This conjured matter (information [love]goal) encompasses the presence that accounts for semiotic agency as a thing.

0332 What does that imply?

As [strife] acquires information, [love] moves closer to its goal.