0001 The book before me is a paperback, published in 2024 by Bloomsbury Academia (London, Dublin, New York) with the subtitle: How to Be a Real Materialist. The author, Slavoj Zizek, is one of the most entertaining intellectuals on the circuit for the contemporary left.

The inner panel of the cover claims that this book is Zizek’s most extensive treatment of theology and religion to date.

This is enough to inspire me to test out Zizek’s analytic expertise.

Surely, Zizek offers food for thought.

0002 In order to pluck the… um… fruit from Zizek’s tree of knowledge, one should proceed to the final chapter, titled, “Conclusion: The Need for Psychoanalysis” (pages 235-266). I know that that sounds like cheating, but a more extensive examination of the remainder of the book is promised.

0003 What does the label “Christian atheism” imply?

First, when the Son dies on the cross, the Father dies as well.

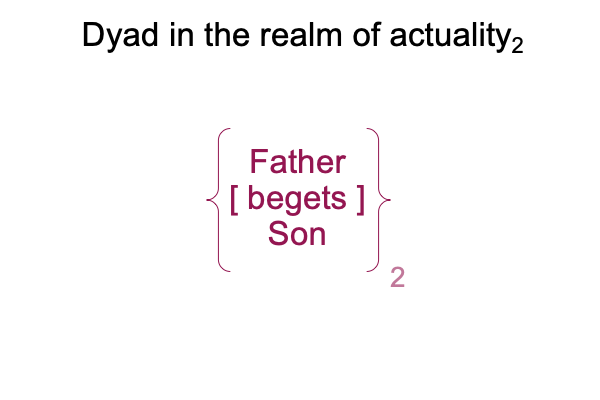

If I frame the relation of Father [and] Son as a hylomorphe, a dyad consisting of two contiguous real elements, the two real elements are Father and Son and the contiguity, placed in brackets for proper notation, should be something like [begets]. Here is the resulting hylomorphic structure.

0004 This actuality… er… hylomorphe… is typical for Peirce’s category of secondness. Secondness consists of two contiguous real elements, as discussed in A Primer on the Category-Based Nested Form, by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues.

Secondness is the dyadic realm of actuality. Secondness prescinds from firstness, the monadic realm of possibility. Thirdness, the triadic realm of normal contexts, signs, mediations, judgments and so on, channels this precission. Thirdness brings secondness into relation with firstness. Such is the nature of the category-based nested form.

0005 So what happens when the Father, the thesis of the Old Testament, begets His Son, Jesus, his antithesis in the New Testament? Well, the good book tells the stories. Jesus ends up dying on a cross after crying out, “Father, why have you abandoned me?”

Surely, this is a psychic trauma that Lacanian psychoanalysis might be interested in. But above, there is only the divine actuality2. Actuality2 is encountered, it is not understood. In order to understand an encountered actuality2, one needs to figure out a normal context3 and potential1. The category-based nested form has all the ingredients for understanding (that is, all three categories get labeled and constitute a single triadic relation).

0006 Zizek says that, when the Son dies, so does the Father.

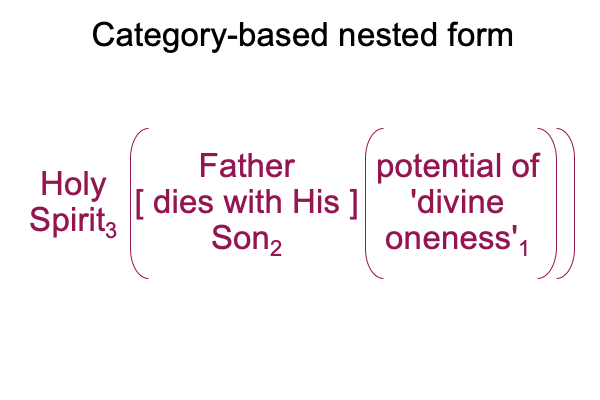

Here is a picture of this actuality2, along with my guesses concerning the normal context3 and potential1.

0007 The normal context of the Holy Spirit3 brings the dyadic actuality of {the Father [dies with His] Son}2 into relation with the monadic possibility of ‘divine oneness’1, that some Christians want to call “Love”. But, Muslims seem to call, “Allah”.

Even though Zizek is well-trained in Lacan’s psychoanalysis, he is also versed in Hegel’s philosophy and Marx’s materialism. So, he notes that after Jesus dies… and the Father dies too… Christ becomes the Holy Spirit, as a new emancipatory collective (page 242). Well, he calls the Holy Spirit, “the Holy Ghost”, so it makes sense that Jesus would be the Ghost instead of His Father, if that helps.

0008 So who or what is this emancipatory collective?

Uh oh, is it the so-called “bride of Christ”?

0009 The actuality of Father [begets] Son2 associates to an encounter in the Real.

How real?

0010 On one hand, Protestants make the point that the Old and the New Testaments are more real than the Catholic church. But, there is a distinction between an encounter (actuality2) and understanding (a complete category-based nested form). Surely, the Old and New Testaments witness encounters. I wonder whether the Protestants can pass to understanding. There are questions about the words. What do the words in the text signify?

Zizek takes the words literally when he says that Jesus, the Christ, becomes the Holy Ghost. But, there is a lacunae, because the Holy Spirit3 is the one who speaks from the cloud above the soon-to-be severed head of John the Baptist. There, in the Jordan River, the king of kings is baptized. The Holy Spirit3 is already present as a purely relational being, the normal context for the actuality of {Father [and] Son}2.

0011 The Catholic church, on the other hand, codifies one particular encounter, the Eucharistic sacrament (otherwise called “the Mass”). Yes, Catholics can join in the potential of divine oneness1 through this sacrament2, which celebrates the simultaneous death of the Son and Father.

“Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” applies to the Father as well as all humanity. Just as elites of Roman Guard and Second Temple are monsters for murdering Christ under the pretext of their laws, the Father is a monster for offering his own Son as a sacrifice. During the Mass, we humans remind ourselves of our own culpabilities and the Father, too, reminds Himself of His own, by transubstantiating the consecrated bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ. Yes, the Father brings Jesus back to life, at the Resurrection and the consecration.

0012 The Mass is far more twisted than most theologians will admit. But, a Lacanian can concede the deal. The Father allows us into mystical union through the Son while saying, “If you eat of my monstrosity, I will accept your monstrosities.”

Of course, some qualifications apply.

That is what the sacrament of confession is for.

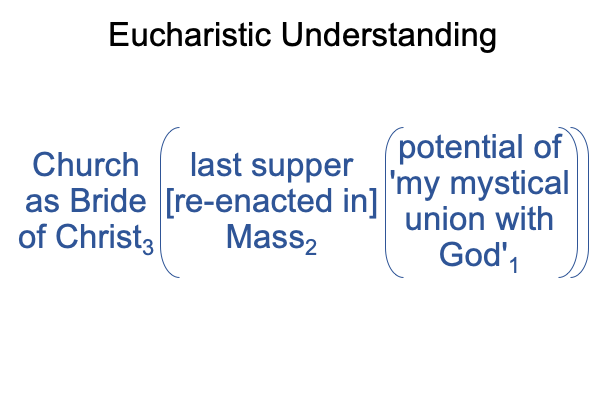

Here is a picture for the emancipated collective that associates to the Holy Ghost.

The triadic normal context of the church, as the Bride of Christ3, brings the dyadic actuality of {Jesus’ last supper [re-enacted in] the Mass}2 into relation with the potential of ‘my (human) mystical union with God’1. The sacraments are mediators between human and divine.

0013 Well, this is not precisely what Zizek has in mind.

Zizek mentions the Holy Ghost in light of Freud’s death drive. Freud uses the term, “death drive”, to label repetition disorders that basically say, “I am still alive.” Or maybe, “If I keep doing this, I will not die.”

It’s like the fellow who loves fishing, encounters a massive illness that almost kills him, then returns to fishing. I am still alive. The death drive creatively sublimates the trauma. Fishing becomes an obsession. Fishing borders on the sublime. The fish that struggles against the line is a symbol. The life that the fish fights for is imaginary, because all of us are mortal. But, one never knows until death arrives. The death drive continues to repeat until we have reached the destination.

0014 So, what precisely does Zizek have in mind?

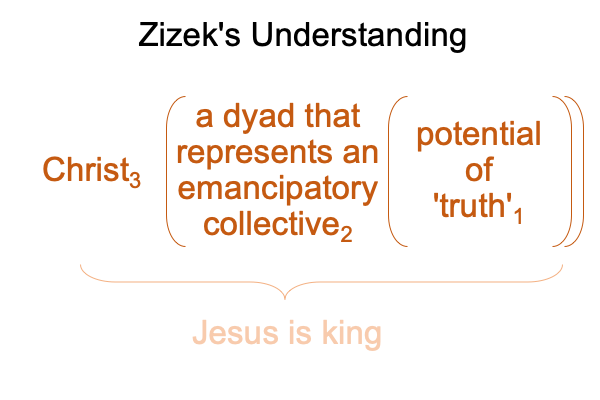

Well, I suppose that Zizek wants to capitalize on the idea of the Holy Spirit as an “emancipated collective” for his socialist theory. Does Zizek buy into the hocus-pocus of the Catholic church as the Bride of Christ3? Or, does he want to make Christ2, who belongs to the category of secondness, into a figure3, belonging to the category of thirdness, that operates on the potential of ‘truth’1?

0015 Zizek’s configuration is corroborated at the very end of the chapter (page 265) when he comments on a 1918 poem, titled “Twelve”, by Aleksandr Blok. At the end of this poem, an apparition of Jesus walks before a team of twelve Red Guards, patrolling the snow-filled streets of revolutionary Petrograd. Christ is not a leader2 (in the realm of actuality2), Christ3 is a shadow who contextualizes the actuality of a group of comrades2 who, in turn, both emerge from (and situate) their Cause1 (the potential of truth1).

So, I wonder, what type of king is this?

Does the kingdom of God dwell among us in such a strange and mysterious manner?