0103 Here is another example.

Some common folk notice that, after throwing a soggy log onto a campfire, a salamander or two runs out. Hmmm. What is a schoolman to say to that?

It is the same problem as flowers and bees, with one more substance. The fire is real. The log is real. The salamander is real. Also, the relation is real. But, this relation is real only because someone notices ‘something’ about the fire, the log and the salamander.

0104 The schoolman says the following.

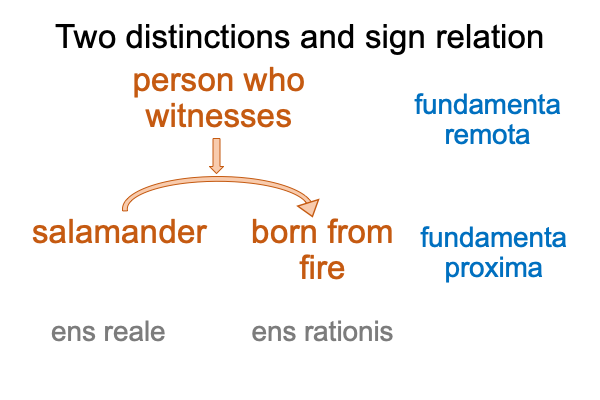

The remote fundament is the person who sees the event.

The proximate fundament is the salamander and the fire.

The mind-independent being is the salamander, who runs right out of the fire… er… steaming log.

The mind-dependent being is the notion that salamanders are born from fire.

0105 The schoolmen have yet to figure out that their crucial distinctions actually describe a relation with three termini.

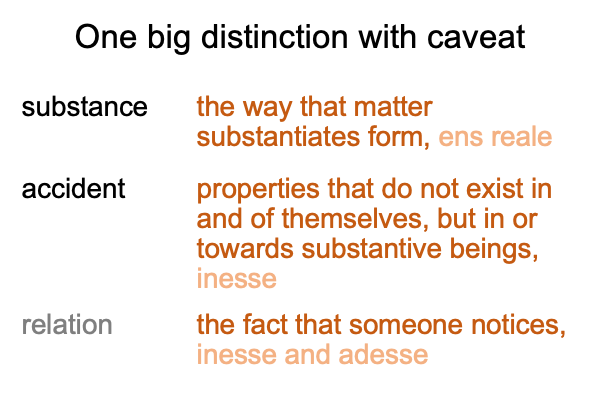

0106 Adding to this mix is the distinction between substance and accident.

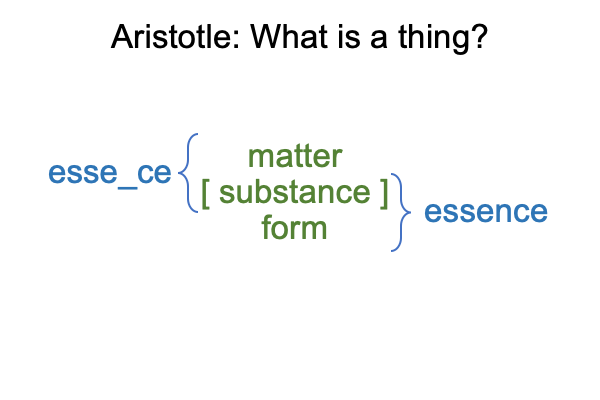

Here, it helps to remember Aristotle’s foundational dyadic actuality.

0107 For the log and fire, the substance is the contiguity between matter and form. That is straightforward. For the salamander, its substance is “in esse” the fire, in so far as the fire substantiates the form of the salamander.

Consequently, the relation between the salamander and fire is “in esse“. This relation belongs to ens reale, and conveys a sense of esse_ce (which is my way of Anglicizing the Latin term, “esse“).

Plus, the relation between the the salamander and the observer is “ad esse“, from the proximate fundament towards (in Latin, “ad”) the remote fundament. This conveys a sense of ens rationis.

0108 What a mess!

Deely winds his way through the terminology of subjective (the subject is ens reale, mind independent being), objective(the object is ens rationis, an accident noticed by someone in regards to the subject) and intersubjective (the fact that someone notices ‘something’ about the subject is itself a mind-independent being).

0109 In the 1000s, schoolmen put ens reale front and center. Why? They want to distinguish ens reale from ens rationis. The idea is to separate the subject from the object.

By the 1600s, the Baroque scholastics examine the intersubjective, the ens rationis (of the specifying sign) that inspires the ens reale (of the exemplar sign), while Descartes’ vision of a mechanical philosophy takes Northern Europe by storm.

0110 In section 8.3.3, still working towards the 1600s, Deely slows to a crawl.

The distinction between substance and accident veils the triadic sign-relation.

Things have or are substances. The technical terms are esse, substantiated being (for me, esse_ce) and ens, being as being (regardless of substantiation).

Colors or adornments are accidents that depend on the subjectivity of a subject. The technical term is in esse or depending on the esse_ce of another. Esse_ce is equivalent to matter [substantiating]. Note that an adornment does not alter the essence, the [substantiated] form.

Sign-relations may depend on the subjectivity of a substance as one terminus. But, um… it may also depend on the subjectivity of an accident. The subjectivity of the sign-vehicle associates to ens reale. The objectivity of the sign-objectis altogether confounding, because it is ens rationis. It depends on someone noticing. That someone serves as the ens reale that makes ens rationis possible.

0111 What is the substance of a sign relation?

The fact that the question confuses is no accident.

It is in esse, in so far as one terminus is indifferent to substance or accident, as long as there is a substance or accident.

It is ad esse, in so far as another terminus depends on someone noticing. Plus, it does not care who that someone is.