0039 Intersections are inherently mysterious.

0040 Newson and Richerson are scientists, so their big picture tries to get around the mystery of two actualities constituting a single actuality. One of the tricks is the hidden ingredient. Another trick is to replace the content-level hylomorphe, DNA [codes for] body2a, with a single word, “gene“2a.

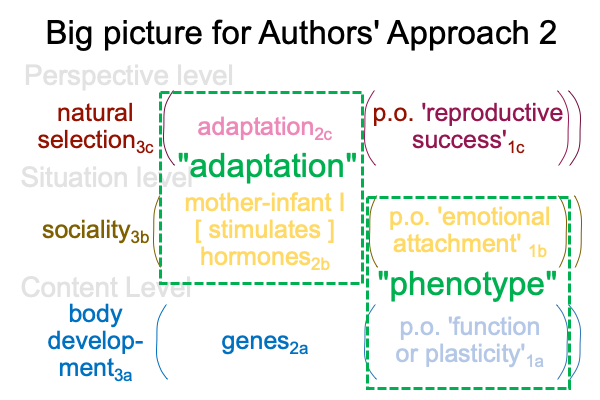

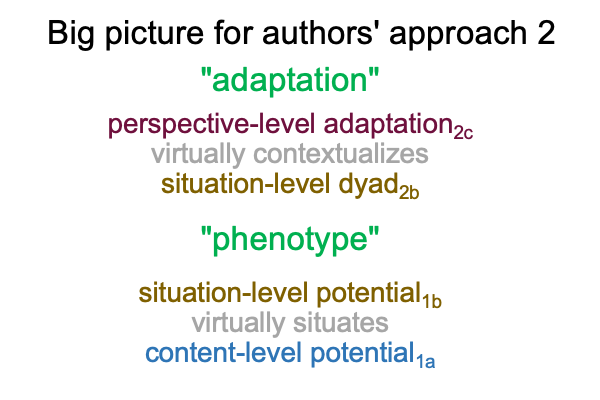

0041 Two novel definitions allow me to further describe their approach.

A “phenotype” is the situation-level potential1b virtually situating the content-level potential1a.

An “adaptation” is the perspective-level actuality2c virtually contextualizing the situation-level actuality2b. The situation-level actuality2b ranges from social interaction [stimulates] hormone response2b to culture [informs] brain2b.

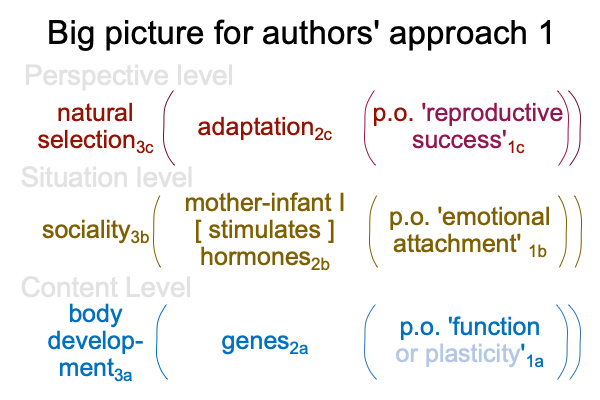

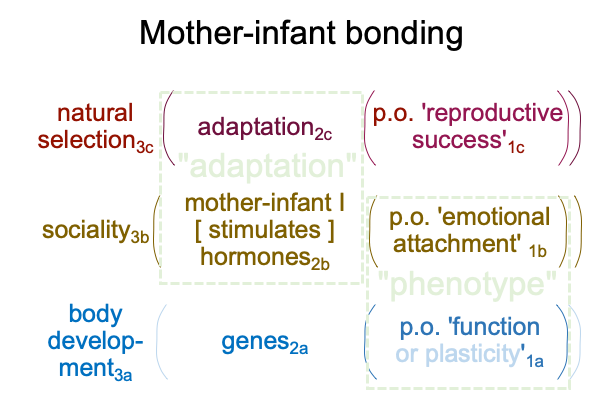

0042 Now, the theoretical construct as a three-level interscope looks like the following.

0043 So, an “adaptation” is a perspective-level actuality2a (arising from the potential of reproductive success1ccontextualizing an instance, ranging from social interaction [stimulates] hormonal response2b to culture [informs] brain2b. Here, the “adaptation” includes the ways2c that mother-infant interaction [stimulates] hormones2b increases reproductive success1c.

Here, a “phenotype” is emotional attachment1b virtually emerging from (and situating) an innate2a function1a.

0044 Consequently, the terms, “adaptation” and “phenotype” are no longer independent actualities, as noted in the previous blog. Instead, they are labels for two category-crossing pairs, one for actuality and one for potential.

For “adaptation”, sociality3b, reproductive success1c and natural selection3c are bound. The perspective-level actuality2carises from reproductive success1c, a necessary, but not sufficient cause. The situation-level actuality2b is a hylomorphe, ranging from social interactions [stimulate] hormones to culture [informs] brains.

For “phenotype”, body development3a, genes2a, function versus plasticity1a and ‘something’ social1b are bound. ‘Something’ social1b can support social interactions2b or culture2b. The brain and body3a will innately display either functionality or plasticity or some combination of the two1a.

0046 Here is the picture for mother-infant bonding, which displays function as the content-level potential.

0047 Chapter two discusses the last common ancestor between humans and chimpanzees.

Newson and Richerson discuss some ways that social interactions may grade into (what scientists might call) culture.

0048 The first concerns vocalizations. Yes, vocalizations may be social interactions. Or, they may be the product of social interactions. A great ape may want to engage in some interactions and avoid other interactions. These intentions are physically on display when an ape takes the initiative to do something. Something may include vocalizations, but action is everything. Actions are signs of intention.

Newson and Richerson mention vocalizations because (somehow) these creatures have to end up speaking, like we do today. They cannot imagine an alternate pathway, such as the one described in Razie Mah’s e-masterworks, The Human Niche and An Archaeology of the Fall, along with commentaries grouped in the series, Buttressing the Human Niche and Reverberations of the Fall.

0049 The second is group living. In group living, social interactions abound.

0050 The third consists in compromises that accompany group living: hierarchy and alliances

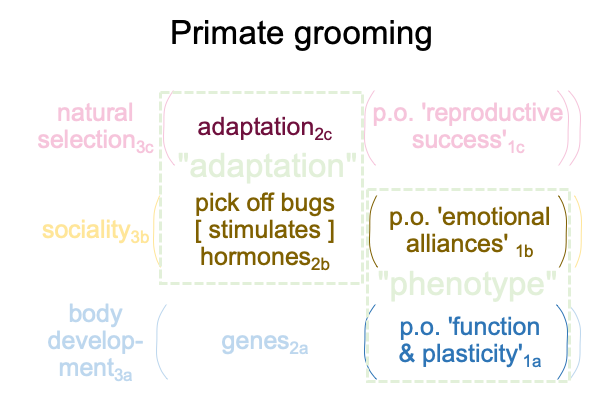

0051 The fourth is grooming, which sustains alliances and fits well into the hormone-release concept of social interaction.

0052 Here, genes2a grant an established hormone-triggering system a degree of plasticity1a. Hormones2b are relaxing and promote emotional alliances1b.

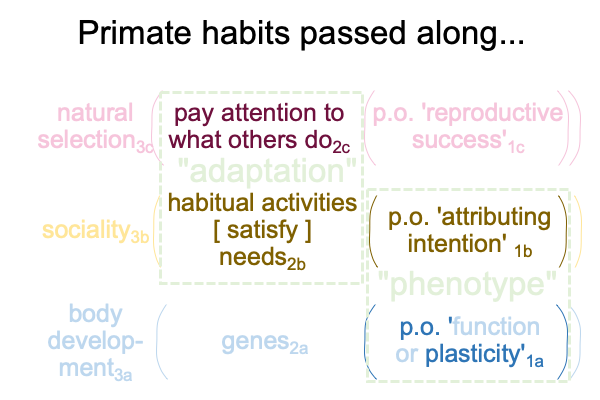

0053 The fifth is culture, which consists in non-genetic inheritance, typically passed from mother to offspring. Here, culture includes how to interact while grooming, as well as how to look for and acquire food. The habits satisfy needs. At the same time, habits [of satisfying] needs2b reflect the essence of the hylomorphe, culture [informs] brains2b.

The “adaptation” concerns paying attention to what others are doing2c when others are engaged in habitual activities [that satisfy] needs (such as finding food)2b. The “phenotype” relies on the potential of neural plasticity1a in order to support the potential of attributing intention1b.