0288 May I state the same material in a different way?

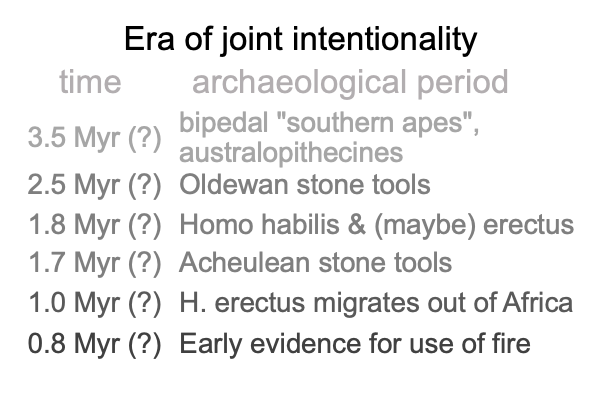

I am still looking at chapter three, concerning the Era of Joint Intentionality.

Here is my reading of the archaeological markers for this evolutionary era. My associations are different than Tomasello’s. During this time, the Pliocene passes into the Pleistocene.

0289 Tomasello asserts that the evolution of joint intentionality associates to the niche of obligate collaborative foraging. This breakthrough insight associates to the social circle of “teams” in the social evolutionary framework of Robin Dunbar.

Razie Mah examines the importance of teams in Looking at Clive Gamble, John Gowlett and Robin Dunbar’s Book (2014) Thinking Big, available at smashwords and other e-book venues. Obligate collaborative foraging and team-workexploits of potentials of mixed forest and savannah between 3.5 and 0.8Myr.

0290 For Tomasello, obligate collaborative foraging entails two interrelated characteristics of teams: interdependence and social selection. Interdependence describes what is happening within each team. Social selection describes the way that each team is exclusive. Each team excludes some members of the band, and later, community. Interdependence expands the ability to exploit time-constrained opportunities. Social selection reinforces two impressions. We work for food. I must compete with others for the opportunity to collaborate.

0291 Each of these characteristics is significant.

0292 First, interdependence entails working together towards a joint goal. Tomasello offers the example of pursuing a stag. A more appropriate example for the start of this era is indicated from the use of Oldowan stone tools.

Oldowan stone tools can be constructed at location by cleverly striking one rock against another in such a fashion that the stricken rock fragments, leaving a section with a sharp edge. This sharp edge can then be used to scrape uneaten meat off the bones of large animals. The sharp-edged core can also be used to break long bones, allowing the extraction of fatty bone marrow. Lots of food can be gathered in a short time by the Oldowan stone-tool team.

0293 Socially, the Oldowan stone-tool team has a joint goal that entails several individual roles. A few labor with sharp stones while the others fend off vultures and (hopefully not) nastier scavengers.

Can the suite of roles be labeled “constrained social complexity”?

I suppose so. Every team has a suite of roles… er… I mean to say… every team exhibits constrained social complexity. Stepping back, a band’s or community’s suite of teams also constitutes constrained social complexity.

No early hominin can gesticulate the label, “constrained social complexity”, using hand talk. What does one pantomime for “constrained”? What does one point to for “social”? I suppose that a shrug of the shoulders can be the hand-talk word for “complexity”.

[BRING CUPPED HANDS TOGETHER][POINT IN DIRECTION OF AUDIENCE][SHRUG SHOULDERS]

Oh, yeah.

0294 The Oldowan stone-tool team selects for individuals with particular cognitive and physiological capacities, such as the ability to keep on task despite distractions and the ability to intrinsically abstract the physics of rocks, sinews and bones. Over generations of successes, these capacities become traits, because those who succeed have greater reproductive success.

Surprisingly, the Oldowan stone tool kit remains the same for hundreds of thousands of years.

0295 Not surprisingly, hominins eventually produce a more thoughtful stone tool, which archaeologists label, “the Acheulean core”. Why come up with a new stone tool when Oldowan stone tools worked well enough? I suspect that selection for the physiological and cognitive capacities for this particular teamwork produces novel adaptations. The improvement is specific to the team. In 1988, two evolutionary psychologists, John Tooby and Leda Cosmides, coin a label for these narrow adaptations. They fashion the term, “mental modules”.

0296 In this regard, see Comments on Steven Mithen’s Book (1996) The Prehistory of Mind (by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues).

0297 Ironically, in chapter five, Tomasello argues that mental modularity does not fit into current empirical evidence of the flexibility of human thinking. But, what about inflexible human thinking? What about accomplishing the work at hand? Don’t evolved mental modules specifically attuned to performing certain tasks (and playing particular roles) come into the picture?

Yes, they do. That is precisely what Tooby and Cosmides propose. Even though Oldowan stone tools remain the same for hundreds of thousands of years, hominins slowly, unrecognizably, become better and better at the work at hand. Indeed, they become better and better at mastering the content level of the three-level scholastic interscope for the way humans think.

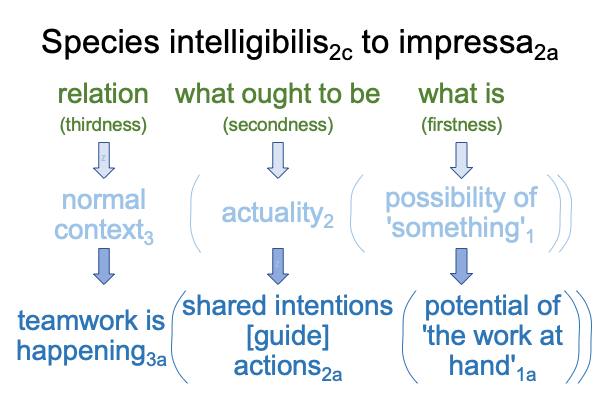

0298 Here is a picture.

0299 What is involved in these slow adaptations into the proximate niches of obligate collaborative foraging and the ultimate niche of triadic relations?

Each team adapts to exploit a specific opportunity that shows up, on occasion and at varying locations, with regularity and abundance. Each team selects for teammates expressing a specific suite of cognitive and physiological traits. Over generations, each team selectively breeds hominins for its “modular” actions.

0300 To me, Tooby and Cosmides’s proposal that the hominin mind is a “Swiss-army knife” of specialized modulesaccords with Tomasello’s vision.

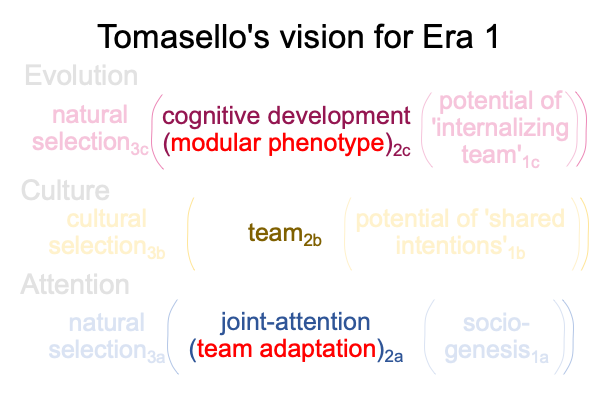

0300 Here is a diagram.

0301 Modularity theory predicts that teams2b select for individuals capable of joining the team. The team2b presumes joint-attention2a as an um… team-specific adaptation2a. The team2b promotes cognitive developments relevant to that team’s particular challenges2c. Today, some cognitive psychologists label these suites of cognitive traits, “mental modules”.

Teams2b respond to opportunities in the proximate niche of the environment and ecology of mixed forest and savannah in Pliocene, then Pleistocene, eastern Africa.

Consequently, these mental modules are products of divergent evolution.

0302 Yet, all teams share a handful of traits in common. Each displays interdependence. Each entails social selection. Plus, each contains hand-talk. This hand-talk is practical, sensible, and aims to request, inform and share what is going on during the drama of team activities. Each team has its own traditions for converting species intelligibilis2c into species impressa2a. Members who cannot hand-talk are left off the team.

The ability of members of teams to hand talk evolves. No matter what the team specializes in, team members become better and better at coupling interventional and specifying signs. Plus, team members get better and better at performing exemplar signs.

These improvements are products of convergent evolution.

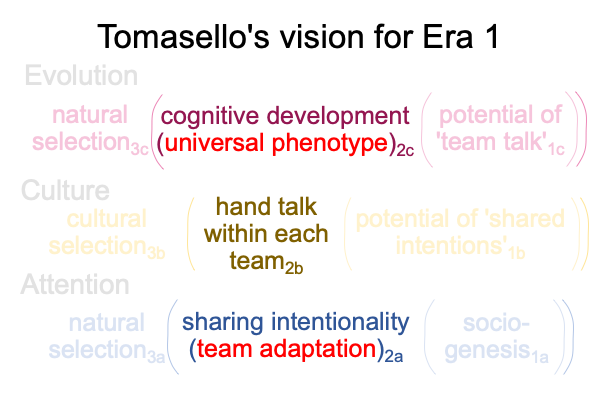

0303 Here is another picture of Tomasello’s vision for the ultimate human niche.

0304 What does this imply?

Modularity theory does not negate Tomasello’s scientific insights.

Hominins work in teams during obligatory collaborative foraging. Teams are diverse.

Joint attention2a and shared intentionality2a are foundational adaptations.

Hand-talk evolves within each team tradition. Hand-talk adapts to an ultimate niche, the potential of triadic relations. Tomasello calls this niche, “sociogenesis”. Proto-linguistic hand-talk and other semiotic processes associated with teamwork may have played a role in the brain reorganization that occurs at the time of the earliest appearance of the Homo genus, near the midpoint of the era of joint attention.