0031 Spoken words are purely symbolic labels.

I ask, “What happens to labels over time?”

One of the quirky theologians of the 20th century, Henri de Lubac, notices that the meanings, presences and messages1underlying spoken words2 change over centuries. He focuses on the words, “nature” and “grace. Both these words are explicit abstractions. They both must be defined3.

0032 What about the term, “inerrancy”?

The first six chapters of Ross’s book (one through six) are devoted to “Biblical inerrancy” and its companion “dual revelation”.

The next five chapters (seven through eleven) argues that the first step in the rescue of “Biblical inerrancy” is concordism. Concordism is the doctrine that um… the two revelations of… is it?… grace and nature?… or Bible and science?… are in harmony, if, for no other reason, they pertain to the same thing.

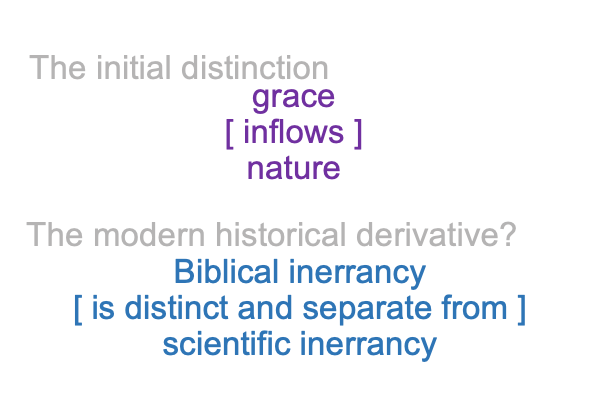

0033 I suppose that is why the old distinction between grace and nature, which is older than Saint Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274 AD), seems relevant.

0034 “Grace” goes with “Biblical inerrancy”. Chapter six discusses this connection. The Psalms declare that the Lord’s word is flawless and true. Jesus embodies the life and the truth.

In a weird sort of way, “flawless” goes with “life”. That would be an esoteric meaning, presence and message. Life is not flawless unless… dare I say… it is compared to death.

Even a mortally wounded creature is alive… until… dead. After I binge-watch dozens of medical podcasts on the most grotesque medical conditions, I marvel that people are alive. There are so many things that can go wrong. That is where truth comes in. The multitude of subagencies within the agent remain true, living, and (relatively speaking) flawless, until, gasp, grace no longer inflows.

0036 “Nature” goes with “scientific inerrancy”. Here, the thing itself (the noumenon) is disregarded. The observable and measurable facets of the thing (its phenomena) are regarded. Ideally, a disciplinary scientific language brings mathematical and mechanical models into relation with data (that is, observations and measurements of phenomena).

To many scientists, when a model works really well, it takes on a truth, a life and a flawlessness of its own. It can take the place of the noumenon, the thing itself. Until, of course, it is proven to be inadequate. Newton’s mechanical physics is a case in point. It worked really well until physicists could not account for the energy spectrum of light coming from a pinhole in a black metal box with a heated interior. How crazy is that?

We still use Newton’s mechanics today, but almost all research goes into figuring out those odd exceptions. The exceptional field is called “quantum mechanics”. Quantum mechanics investigates light, among other things. Atomic and subatomic nature is known through quantum mechanical models.

0037 The upper hylomorphe marks the beginning and the end of my examination of Ross’s text.

The lower hylomorphe suggests that maybe Henri de Lubac is on target.