Looking at Mihhail Lotman’s Article (2017) “History as Geography” (Part 1 of 8)

0744 The article before me is published by Sign System Studies (volume 45(3/4), 2017, pages 263-283) by Mihhail Lotman in the Department of Semiotics at Tartu University, Estonia. The full title is “History as Geography: In Search for Russian Identity”. This particular volume is dedicated to semiotics and history.

0745 The year is 2026. Hundreds of thousands of young men from the currently sovereign states of Ukraine and Russia are now buried in the geography of their sovereign states. The war is senseless to anyone who is not moving money or armaments. A theoretically defensive NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) covets a vulnerable ember of the former USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics). Or is this a proxy war between the USDB (Unsuspecting Subjects Dominated by Bigilibs) and the CCP (Communist Chinese Party)?

Bigilib?

Big-government (il)liberal.

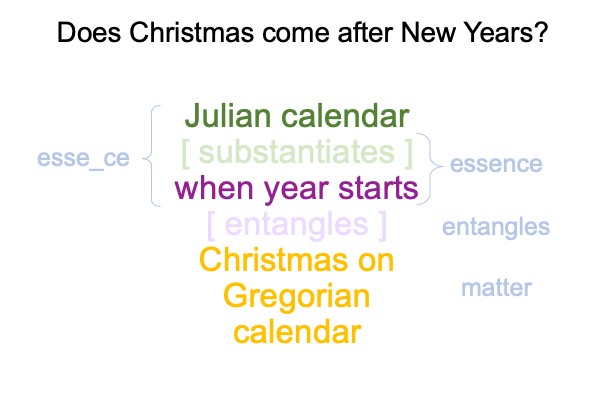

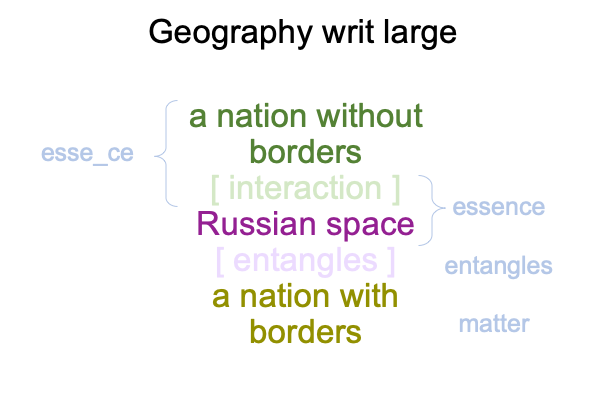

0746 Is Estonia’s geography its history?

Surely, the way the map of sovereign territories alters over the past few centuries is a sign of historical turmoil.

But, do not expect the corporate media to broadcast any information that does not comport with the interests of their clients.

You know, the ones moving money and armaments.

History appears to be irrelevant. Geography and client interests are all that matter.

The form is war.

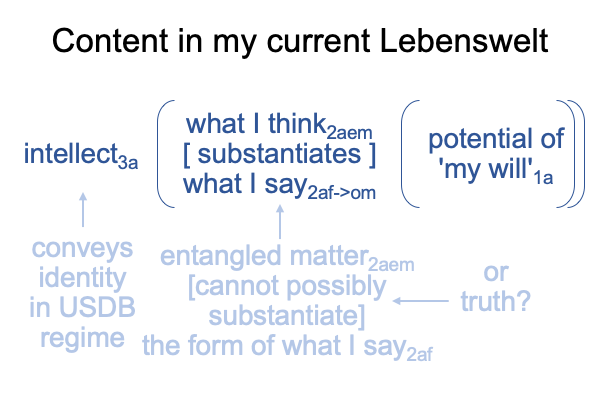

0747 And, the most important territory to be occupied seems to be what people say.

Corporate broadcasters talk about territory. Territory establishes that we all agree upon the ideology. If we speak the same rhetoric about geography in a time of war, then we must all think the same. How obvious is that?

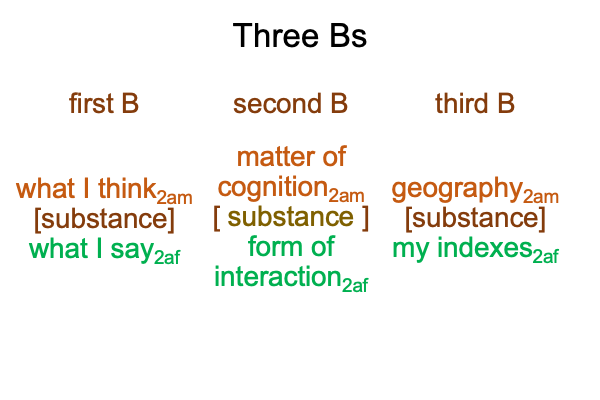

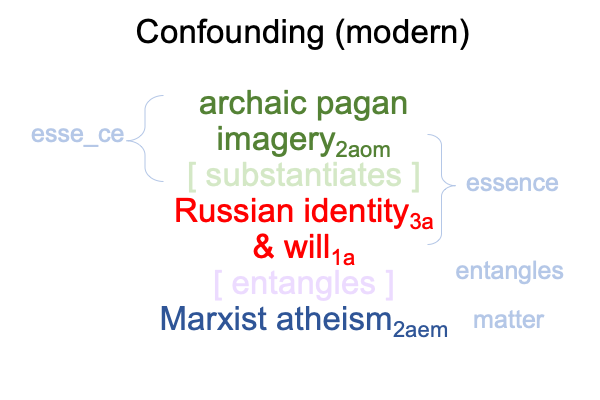

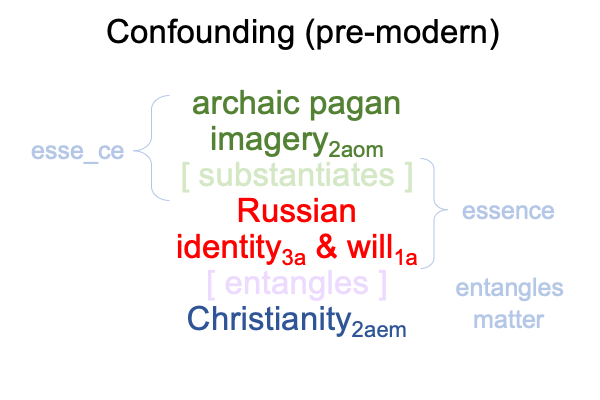

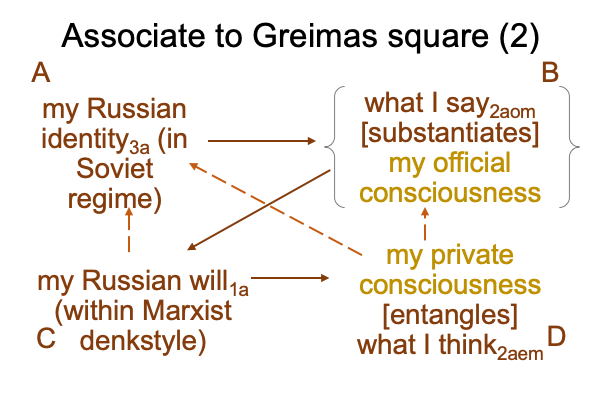

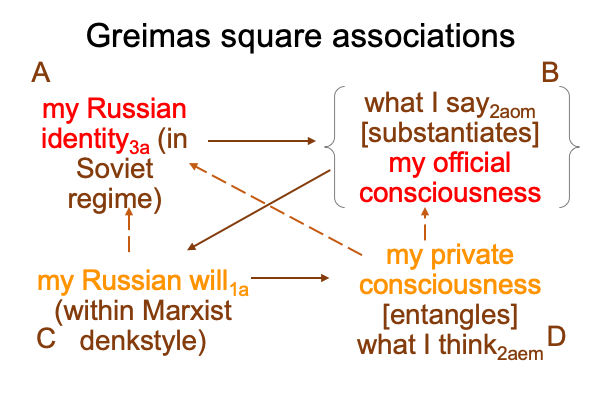

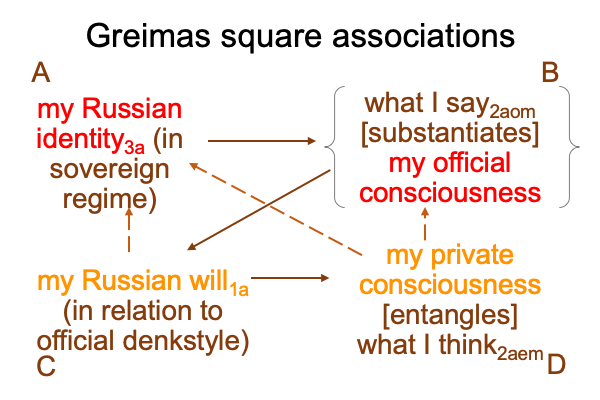

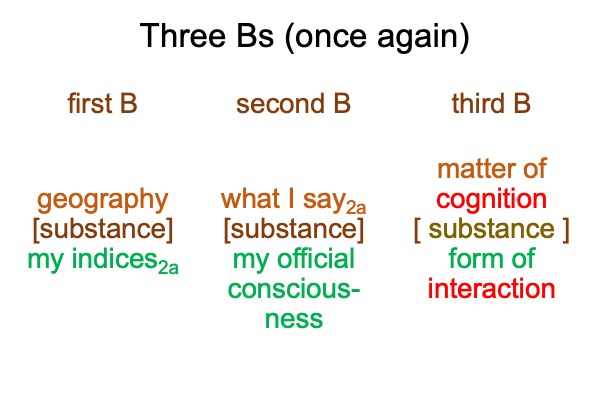

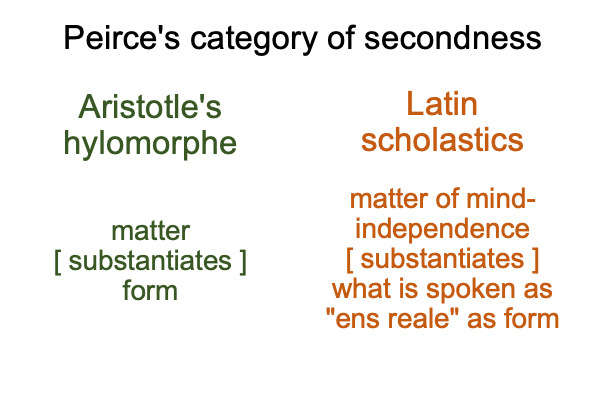

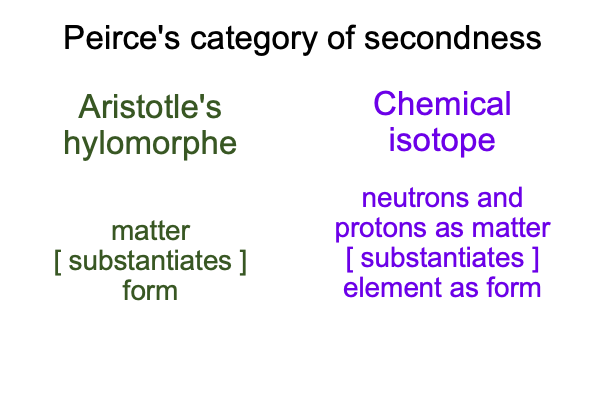

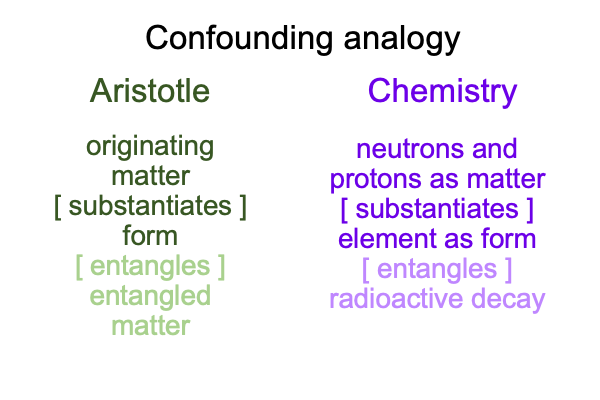

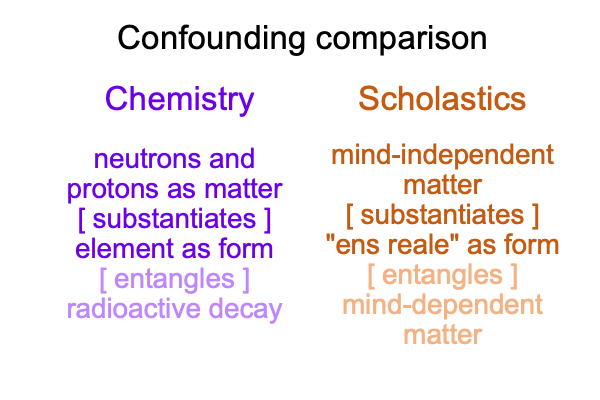

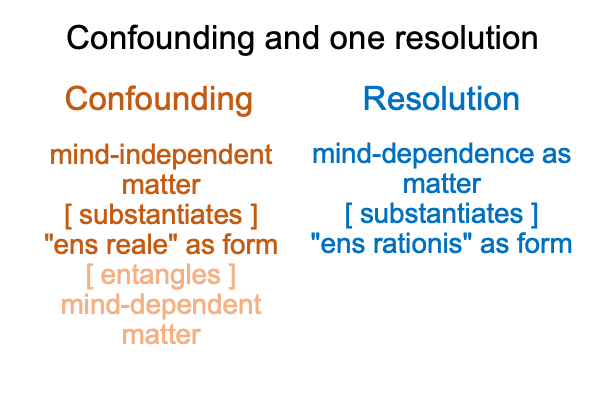

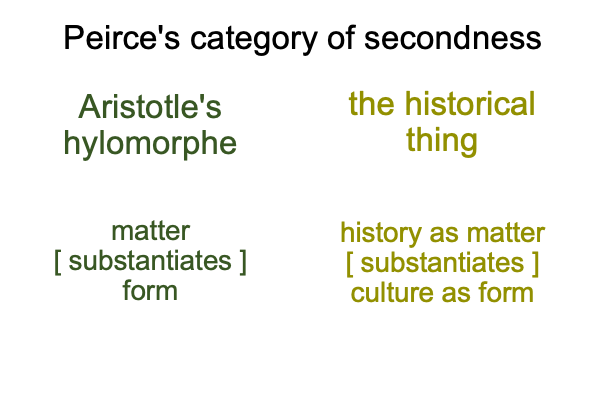

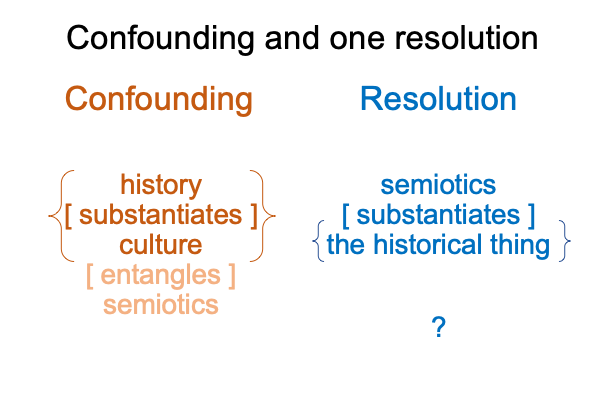

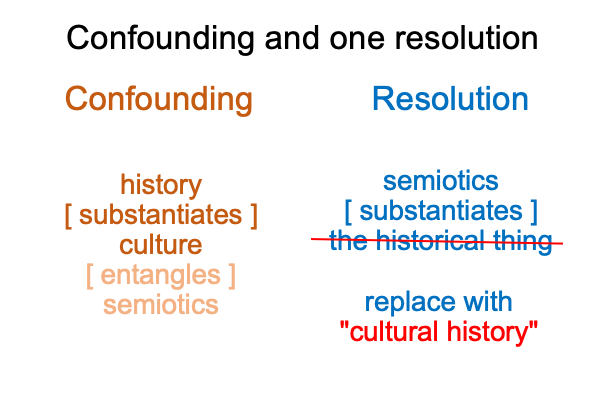

The hylomorphe, where what I say (as form) is substantiated by what I think (as matter), turns out to be very useful for empirio-normative domination. See Razie Mah’s three part e-book, Original Sin and the Post-Truth Condition, available at smashwords and other e-book venues.

0748 So, what are the interests of the citizen?

Who is the citizen?

The citizen is the subject (the empowerer) and the object (the um… “subject”) of sovereign power.

The truth serves the interests of the citizen.

0749 If truth serves the interests of the citizen, then what serves the interests of the unelected bureaucrats?

Oh, it must be the will of the citizen.

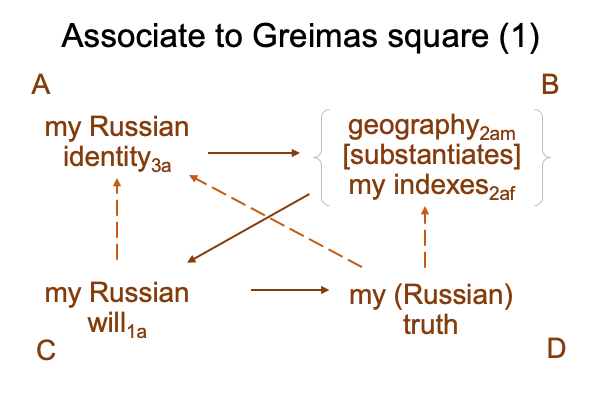

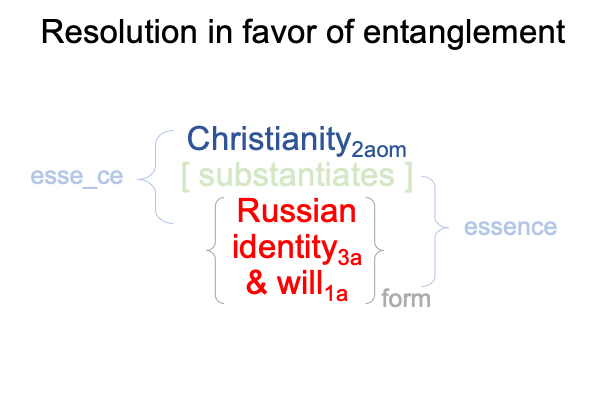

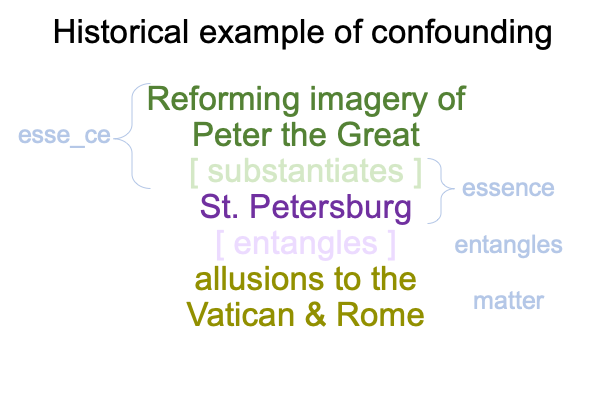

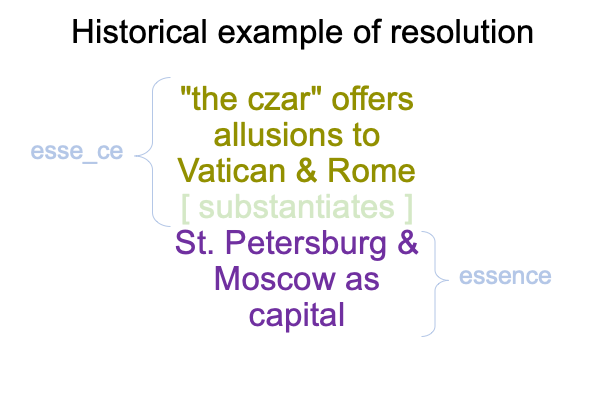

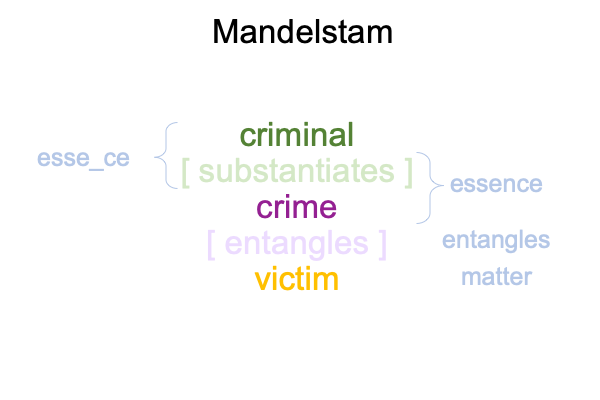

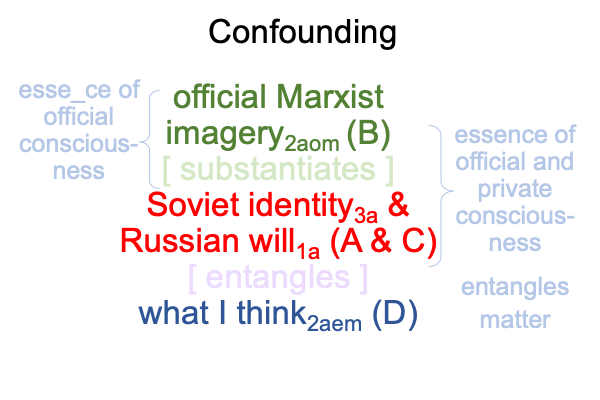

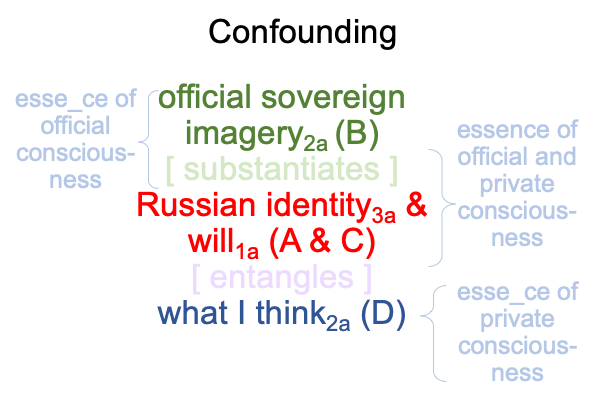

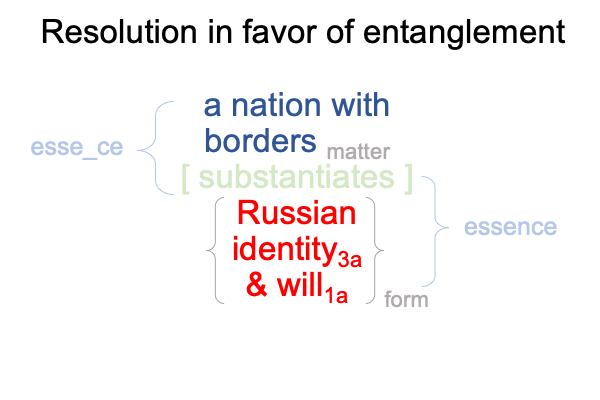

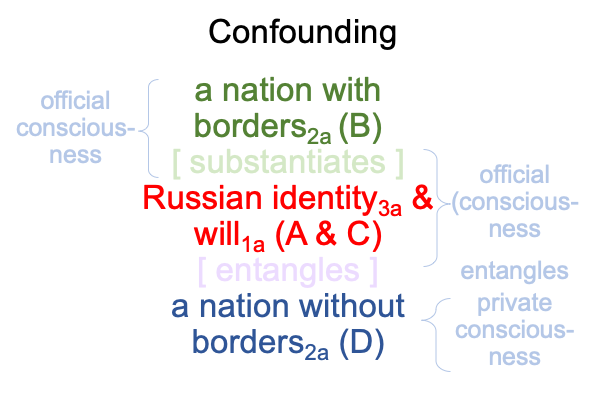

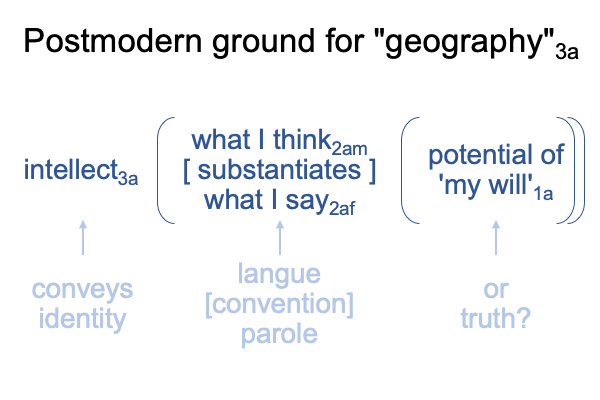

0750 Is the citizen reasonable3a, when allowing experts to decide which tidbits of what I say2af shall be ascribed to um… the citizen’s will1a?

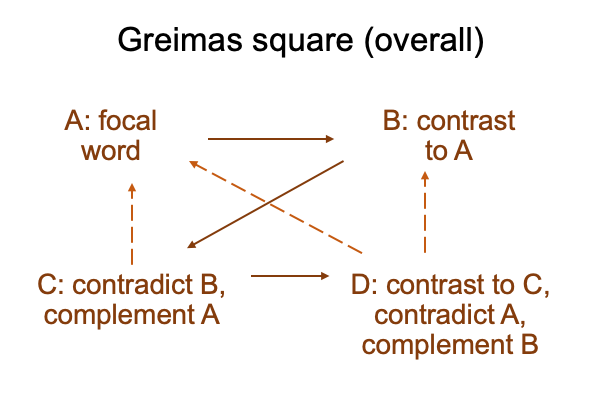

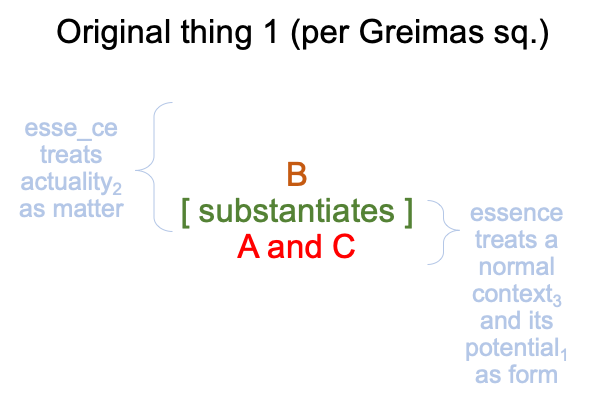

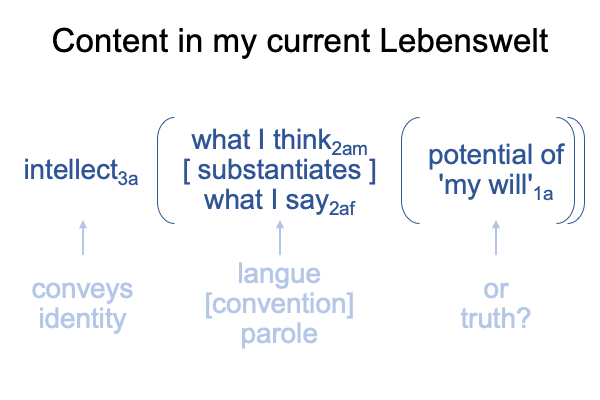

Here is the category-based nested form.

If perplexed, consult Razie Mah’s e-books, A Primer on the Category-Based Nested Form and A Primer on Sensible and Social Construction.

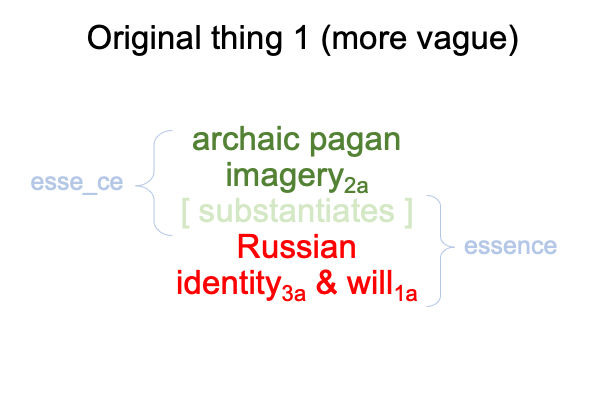

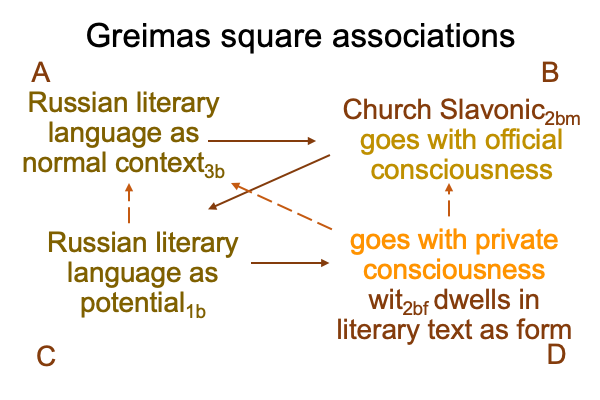

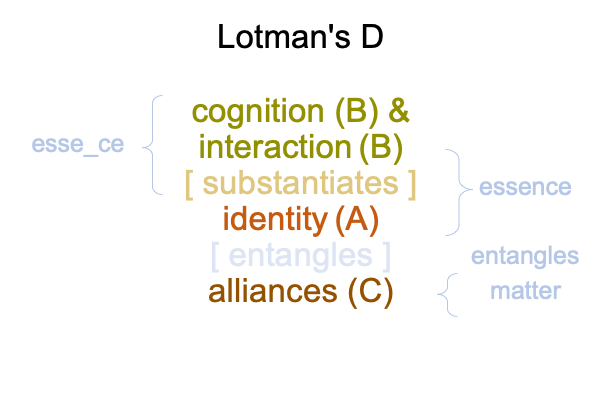

0751 I ask, “What is the author, Mihhail Lotman, searching for?”

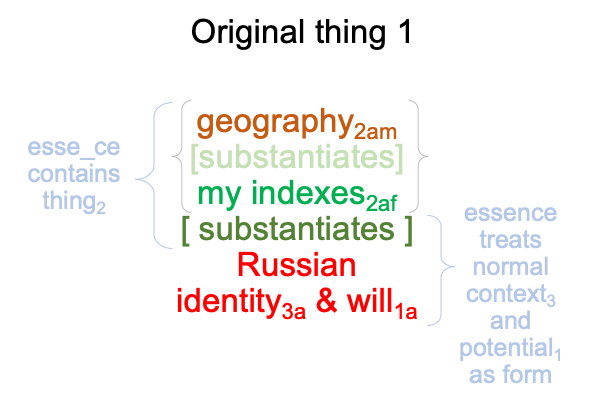

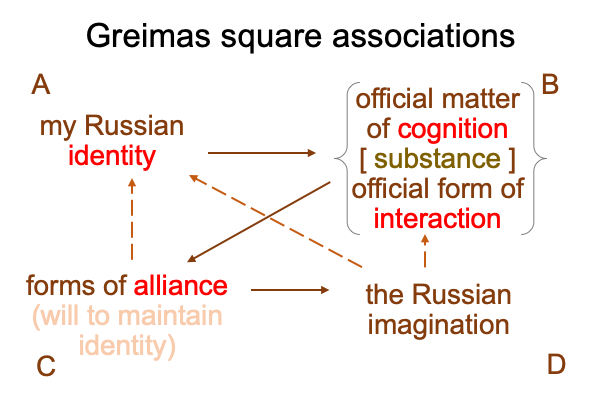

Intellect3a conveys identity. There are two types of identity. One is potentiated by truth1a. The other is potentiated by my will1a.

Notice, that the term, “identity”, which labels my intellect3a based of the potentials of truth or my will1a, cannot be pictured or pointed to. Like all normal contexts and potentials, identity is crucial for understanding. But, what is understanding? Understanding comes when an actuality2 is placed into its proper normal context3 and potential1.

0752 Identity3a is a style of understanding. Is3a it not?

After all, it3a changes with potential1a. Does it3a not?

One cannot picture or point to identity3a.

If one searches for it3a, it3a will always prove elusive, because it3a contextualizes3 and potentiates1 what I think2am and what I say2af.

Better to think2am and speak2af about geography.