Looking at Mihhail Lotman’s Article (2017) “History as Geography” (Part 4 of 8)

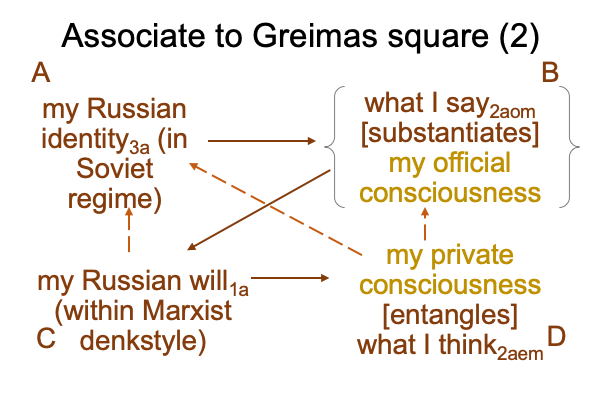

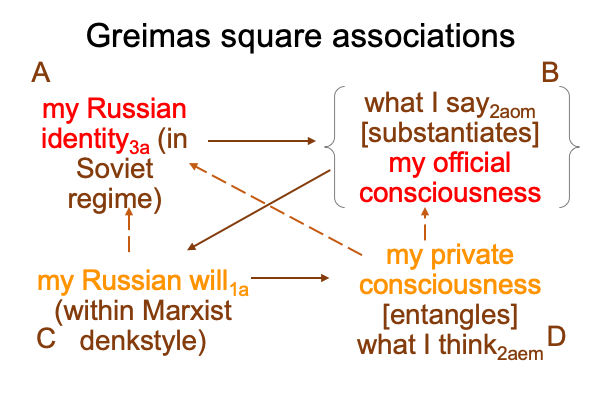

0784 So, there are two models of the binary in Russian theory.

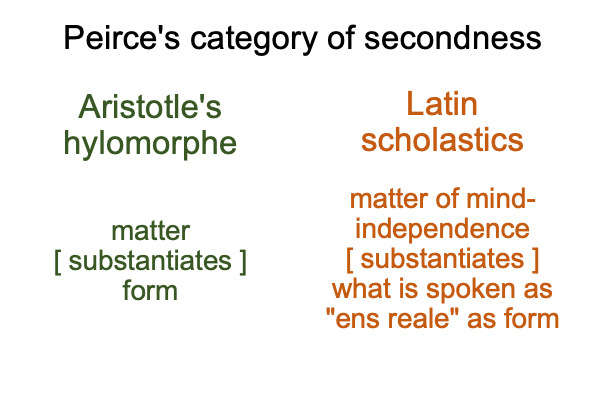

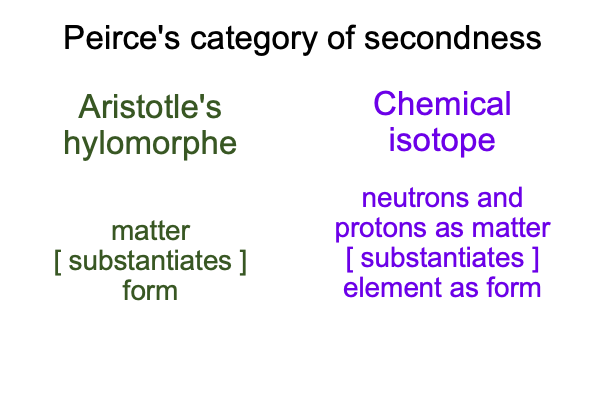

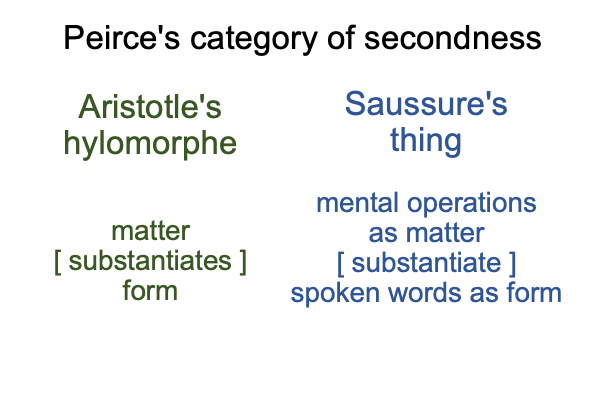

0785 One model conforms to the West, consisting of two equipotent elements, such as Wilhelm Hegel’s trope of thesisand antithesis. As long as the potential of synthesis is suppressed, then a thesis (as matter) will substantiate its antithesis (as form). Perhaps, antagonism is perpetual, because the thesis (as matter) cannot substantiate its antithesis(as form). So each accuses the other. The thesis says, “You are the wrong form.” The antithesis says, “You are the wrong matter.”

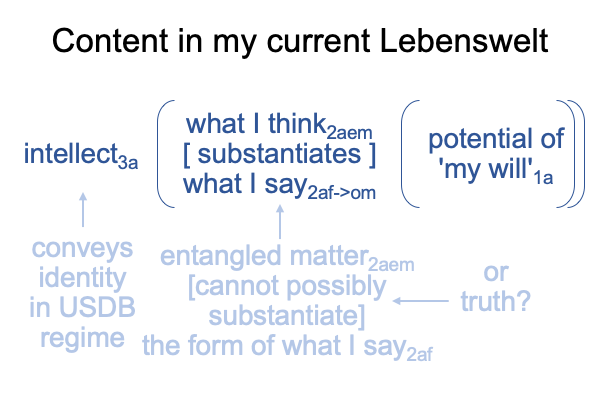

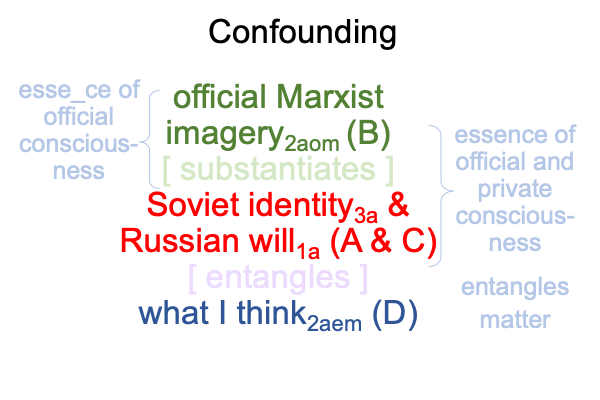

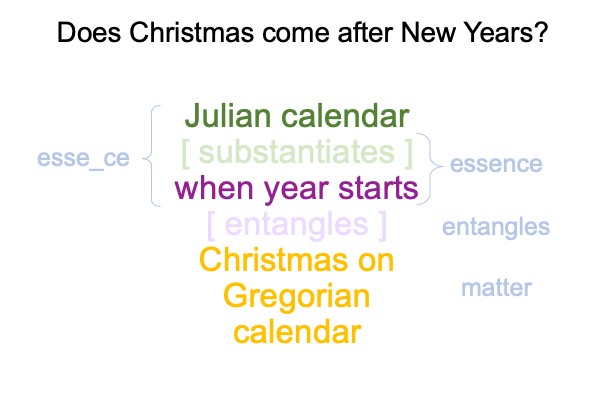

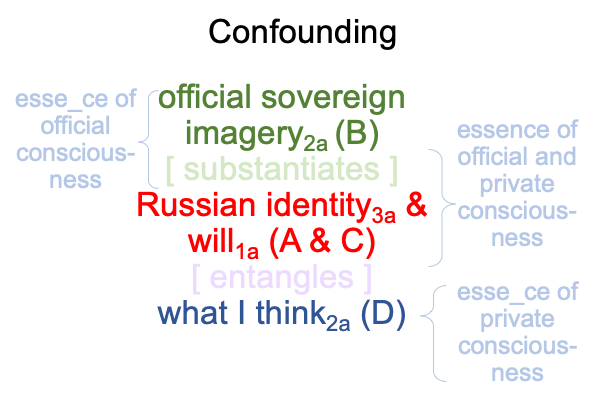

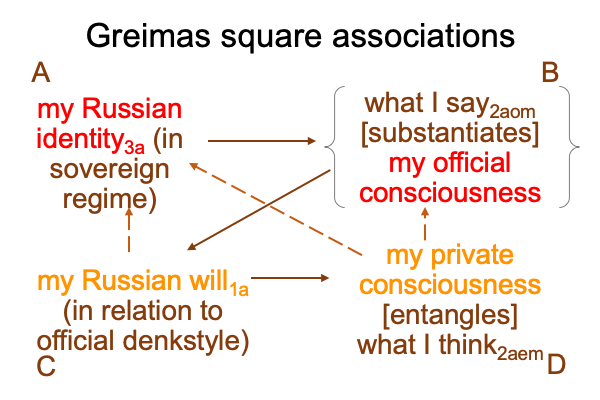

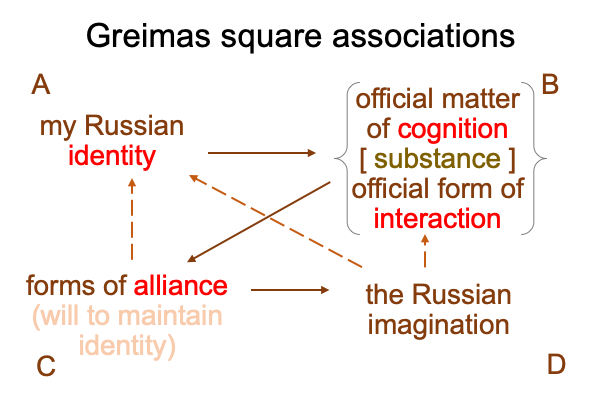

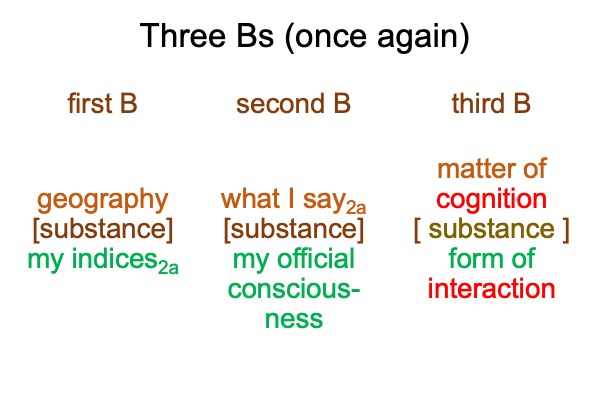

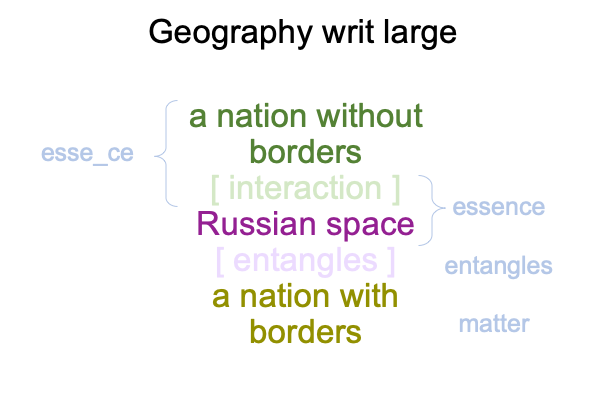

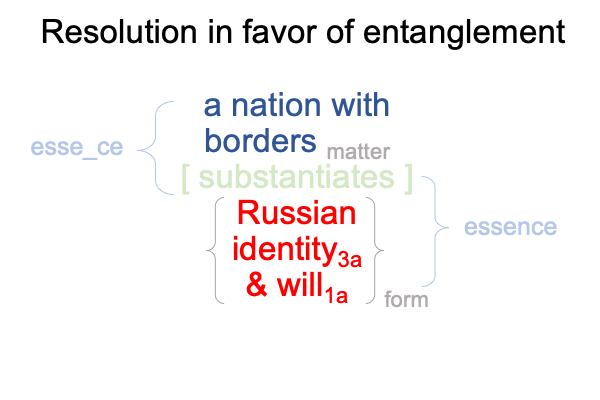

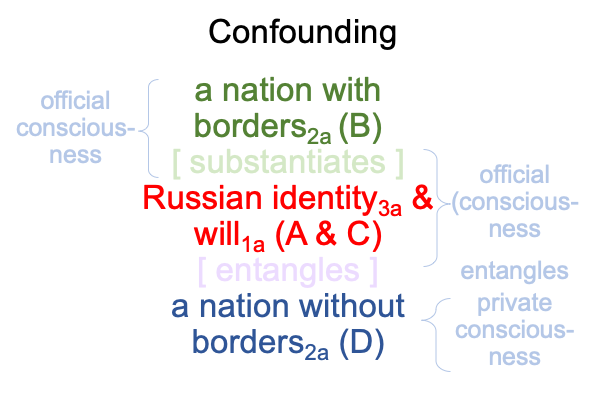

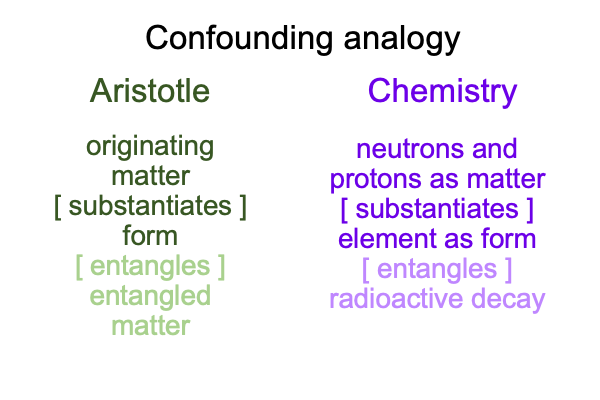

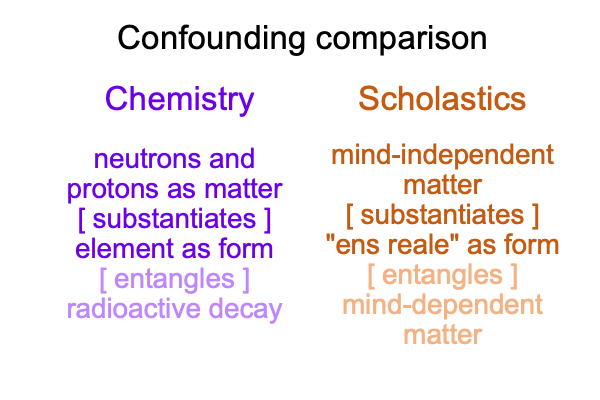

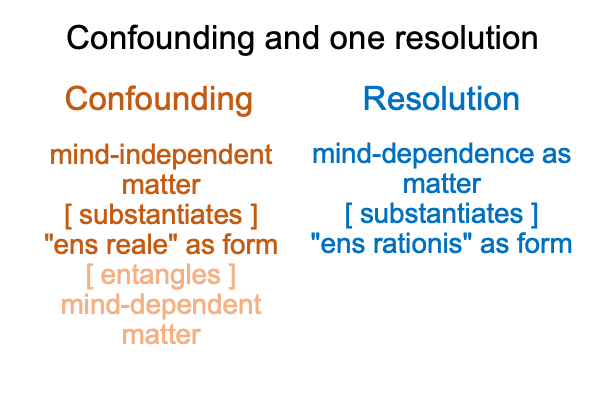

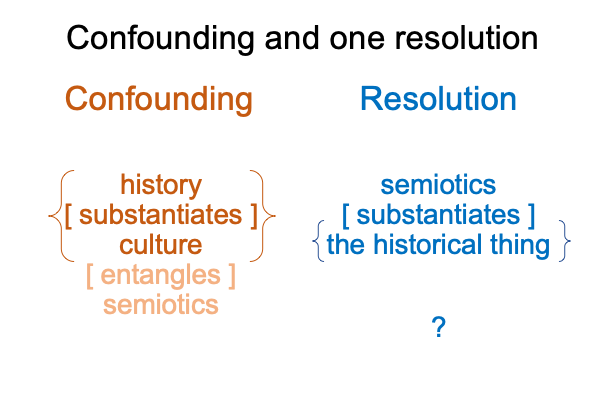

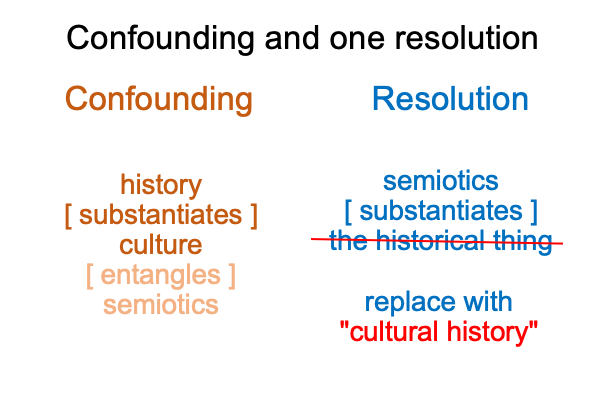

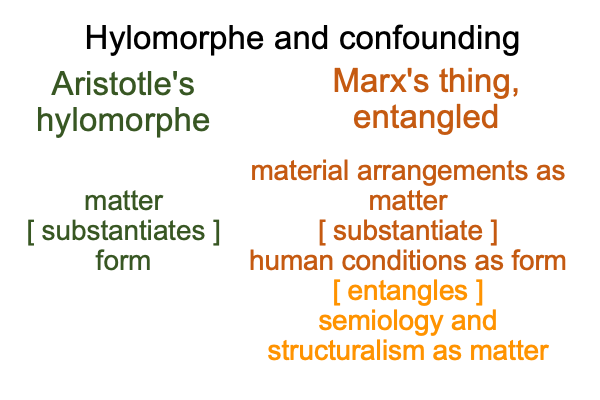

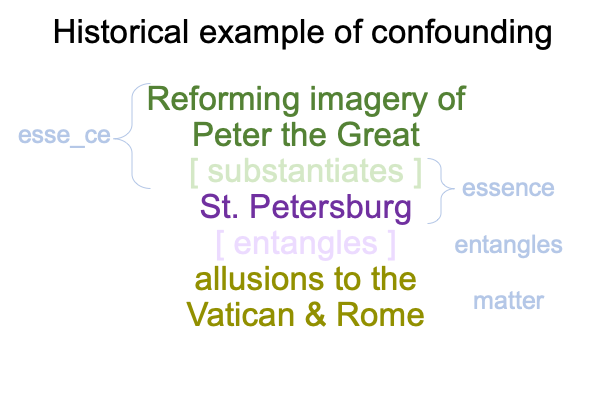

0786 The other model suggests that Russia and other Slavic civilizations embody one form relating to two matters, one substantiating and one entangled. The confounding is dangerous because, unlike equipotent thesis and antithesis (both interested in suppressing the possibility of synthesis), there are two matters that will vary in potency, especially with respect to one another.

The author tells a personal tale where, as an intellectually inclined youth, in rebellion from his academically renown father, considered binarism as a methodological device.

0787 Binarism is a scholarly illusion, so to speak.

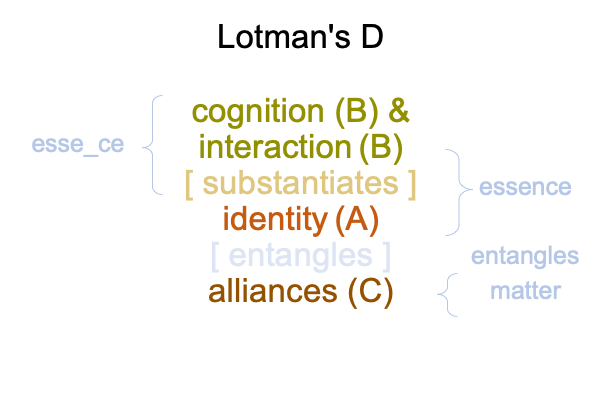

Boris Uspenskij argued with the youth, offering the following historic example where the archaic primal imagery of reform characteristic of Peter the Great ends up literally building a new capital, St. Petersburg, as an icon of the new Russian Identity and Will. However, at the moment when the vision is realized, the capital thing gets entangled with allusions to the Vatican and Rome.

0788 Yes, Moscow… er… St. Petersburg is the Third Rome, but exactly how Vatican-like can it be?

Oh, the St. Petersburg coat of arms clearly alludes to the Vatican’s coat of arms.

Coincidence?

0789 The author goes on to say what happened next.

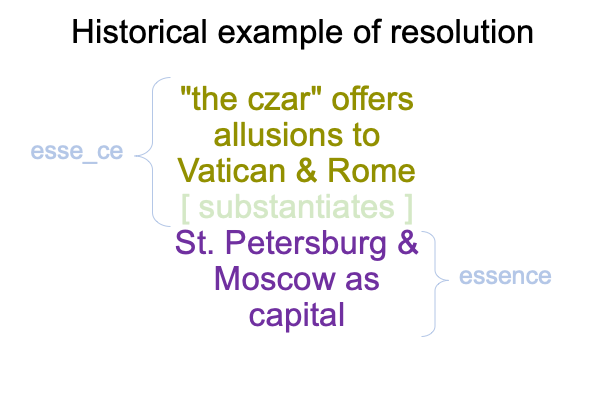

To many, the confounding resolved in favor of entangled matter.

The form (of the capital of St. Petersburg, as well as Moscow) remains the same, more or less.

But now, the form is substantiated by “the czar” (the Russian word for the Latin “Caesar”). The Tsar is a fusion of spiritual and spiritual authorities. I figure that such a fusion characterizes the narod, the prepolitical Slavs, whose rulers spontaneously manifest as both spiritual and physical winners before… you know… the Vikings arrive with their shallow-hulled boats and their ferocious swords. Talk about identity and will!

0790 Yet, the allusions to Vatican (spiritual) and Roman (political) imagery makes it seem like the form of the Russian capital is substantiated by Christianity as matter.

0791 And what gets entangled?

Does the Vatican and the capital of Rome constitute Christianity?

Protestant churches preached against the Czarist’s Christian thing. They, along with the freemasons and other private circles, get entangled as matter.

0792 At this point in the article, the author slides into the methodology of typology, which attaches labels with the goalof “to name it is to know it”.

The typology labels three types of oppositions.

The thesis and antithesis type is “equipollent”.

The confounding and its resolution type is “privative”, “gradual” or (may I add?) “explosive”.

0793 Sometimes the labels are confusing.

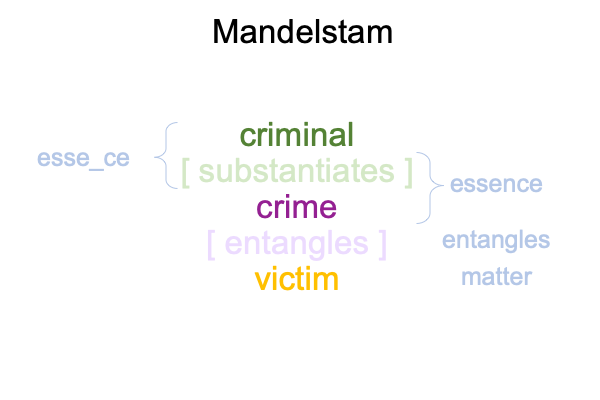

Otto Mandelstam (1891-1938) offers a short story where a criminal (as thesis) and his victim (as antithesis) are regarded as the same. The crime remains as long as justice (as synthesis) never arrives.

While the criminal and victim are equipollent (in terms of matter), they are different when the story is cast as “privative”. The criminal is originating matter. The victim is entangled matter.

The form is the crime.

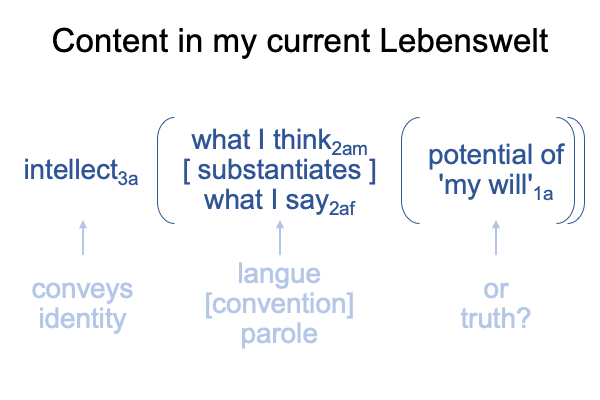

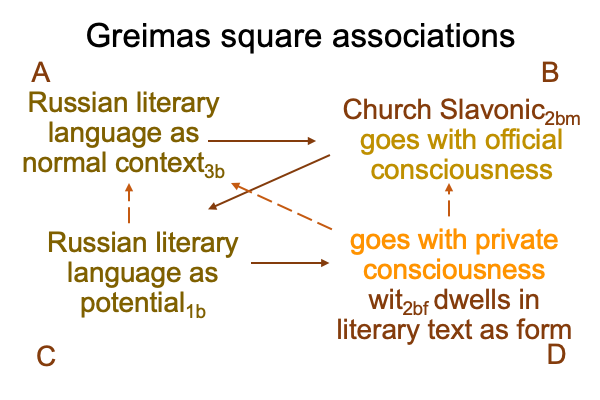

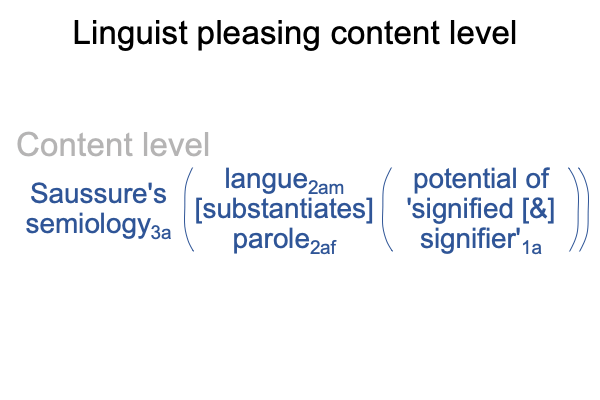

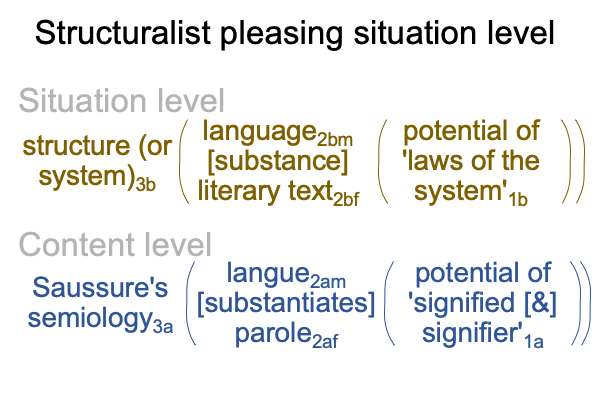

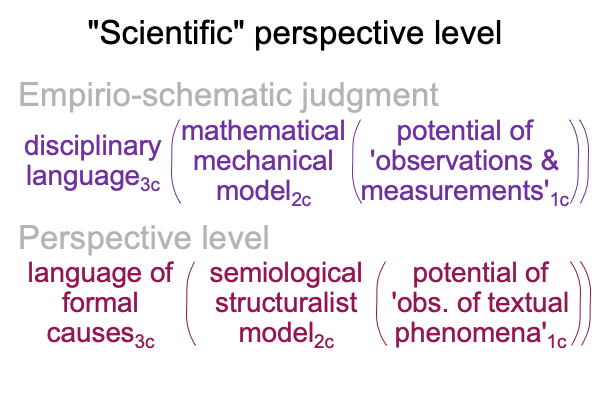

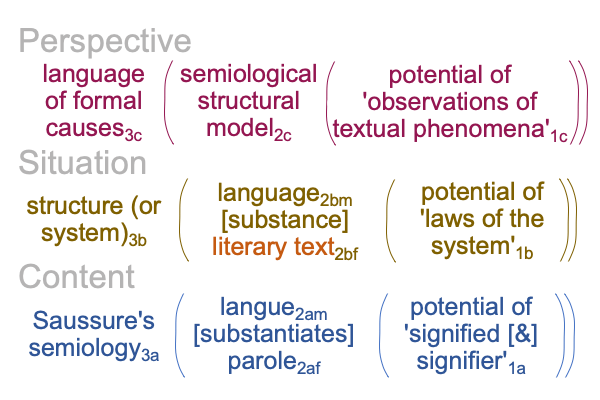

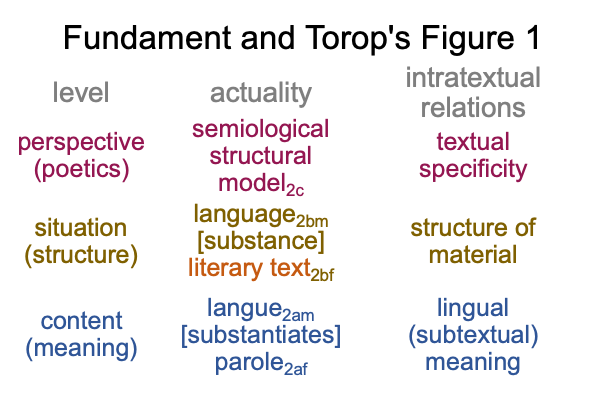

0794 Of course, the author does not detail the above diagrammatic conceptual apparatus.

Instead, he explains the semiotics in ways that are descriptive, rather that diagrammatic.

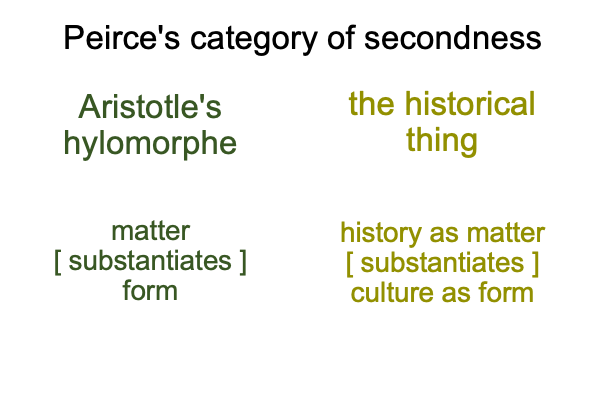

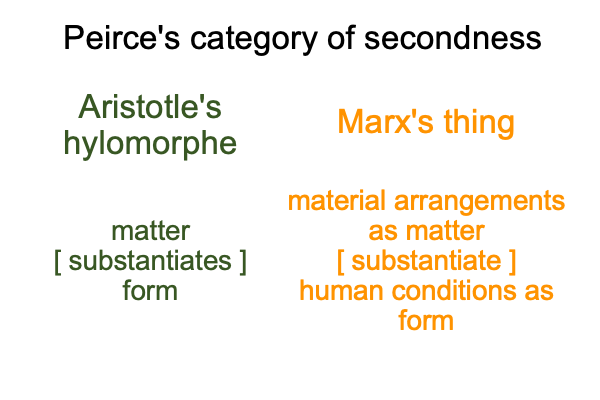

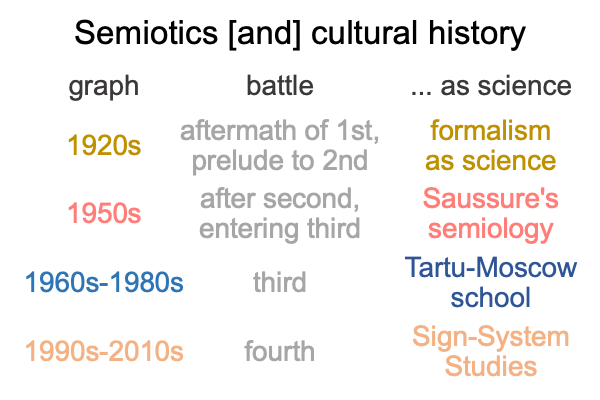

Diagrams assist in illuminating the inherent relationality in both semiology and structuralism.

0795 Perhaps, this examination will assist in constellating a second incarnation of the Tartu-Moscow School of Semiotics.

Diagrams expand the TMS sphere of understanding.